“Birds give me a sense of perspective. Seeing a migrating warbler or swallow, I consider the miles that this small body has travelled; where it’s going, where it has been, and this moment that I am in proximity with it. In turn, I think about all of the organisms surrounding me, and the journeys we are all undertaking. With birds, a momentary glimpse can quickly become a monumental space of contemplation.” -Ben Johnson

Day 1 – Learning Birding

Birding During Isolation

How Bird-Watching Prepared Me for Sheltering in Place

Chimney Rock, on the eastern spur of the Point Reyes headlands in California, is well known for the elephant seals that congregate there. One afternoon, while walking down the path overlooking them, I saw a woman looking through a spotting scope on a tripod, directed out toward the water. It turned out she was watching seabirds. She told me she started bird-watching as she got older because she was analytically minded, loved numbers and words, but struggled with visual memory and acuity and wanted to strengthen those faculties.

Self-Isolation Is Turning Children Into Budding Birders

During the coronavirus crisis, families are discovering their avian neighbors and nurturing the next generation of nature lovers. Before a tidal wave of COVID-19 cases crashed on Chicago, before schools closed and the Illinois governor issued a stay-at-home order, a pair of Cooper’s Hawks took up residence on my family’s block. Their laugh-like cak-cak-cak calls ricocheted around the alleys and sent pigeons flying. My husband, kids, and I saw them swoop from one leafless tree to another, sure, but we didn’t spend much time really noticing them.

Birding Is the Perfect Activity While Practicing Social Distancing

This global pandemic has us all pretty freaked out. Handled responsibly, open space and wildlife observation might be just the balm you need. None of us has been through anything quite like COVID-19, the coronavirus outbreak that the World Health Organization this week labeled a global pandemic. At this moment, more than 137,300 cases have been confirmed worldwide, and at least 5,073 people have died. Markets have tanked. Everything’s canceled. Precautions that once might haveseemed paranoid now feel like common sense.

How I Learned to Love Birding

Blog by Jo Falls – Director of Education

You could say I came to this whole nature thing late in life. Growing up in the Midwest, nature was just something that was – I collected fireflies, watched out for bunny nests in the grassy yard and knew Robin’s eggs were blue. We had a pair of binoculars, bought for my Dad one Father’s Day for a couple of books of S&H Green Stamps in the 1960s, but they were seldom used except for distance viewing at things like sporting events.

As in all activities with a following, adherents differ on the definitions. Our Tucson neighbors were definitely birders, as opposed to birdwatchers. Meaning they would actively seek out a particular bird and travel to distant lands to achieve this goal; rather than just observing whatever came their way. They had an actual bucket list. As a budding anti-establishment intellectual, this all seemed most absurd.

And then one day about 20 years later, I took a job at a little place in NW Tucson called Tohono Chul Park. In 1991 I took over the Education Department and got to know a docent named Lynn Hassler. At the time, she was working on a new field guide to North American birds with her then husband, Kenn Kaufman. In prepping for my first docent program, I turned to Lynn for help with the class on birds and worked with her to establish our first docent-guided birding tours that same year.

Read Full Blog Here

Through our collaboration and friendship, I discovered something – I really liked watching birds. I am sure it is because of the way Lynn taught me to look at them, not as items on a checklist, but as fascinating individuals busy going about their lives. How a Cactus Wren cocked its head when eyeing a potential meal; the nervous wing flicking of Ruby-crowned Kinglets; the territorial displays of tiny Costa’s Hummingbirds; it was about observation and finding meaning in behavior. I learned the birders’ vernacular – LBJs are “little brown jobs,” meaning impossible look-alike sparrows and Butter Butts are Yellow-rumped Warblers – and that by convention, bird names are ALWAYS capitalized.

I bought a pair of bins – binoculars to the uninitiated – Bushnell 7x25s that were barely adequate, but helped get me closer to the action. Lynn and I began scheduling day trips to places like Madera Canyon and the San Pedro River. The more frustrating birding got, the more rewarding it became. Every new bird “learned” was a new friend, someone to get to know – what did they eat, where did they hang out, what distinguished them from a similar species. I “graduated” to better glasses – 8x42s – and began to bird “by ear.” I am sure many of us recognize more bird sounds than we might think – the chug-chug-chug of a car engine turning over (Cactus Wren), chi-ca-go-go (Gambel’s Quail), yip-yip-yip (Gila Woodpecker) or the sound of summer, who-cooks-for-you (White-winged Dove).

So, yes, I did graduate from birdwatcher to birder. Both as part of my job and just for fun, I have been fortunate over the years to bird some amazing places here in the states and abroad. Birding hasn’t become an obsession, except for a particular Russett-crowned Motmot in Mexico, but a comfortable companion.

And by the way, I still have those 1960s 7×35 binoculars.

Birding and Binoculars for Beginners

Birding For Beginners –

Why Bird?

Whether you’re casually taking note of your surroundings, or traveling the nation in search of birds.

Binoculars 101: What are the numbers on binoculars?

Understanding Binoculars: Magnification and Stability

How to get crystal clear focus with your binoculars

Get Going

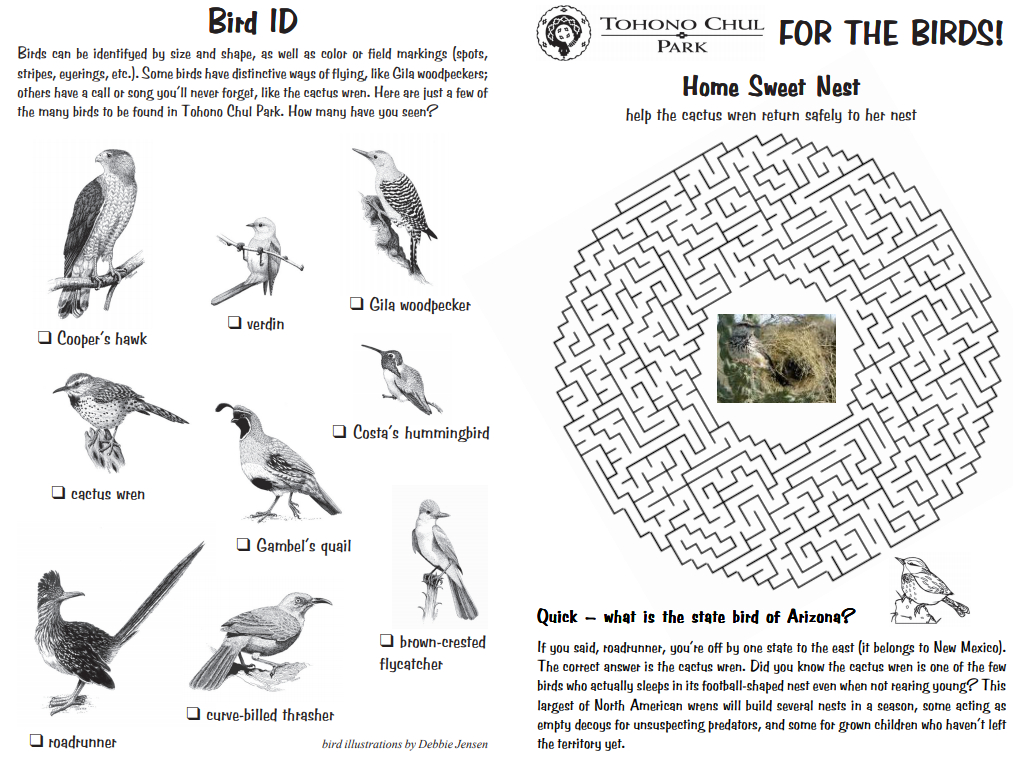

Tohono Chul Bird Activity Sheet

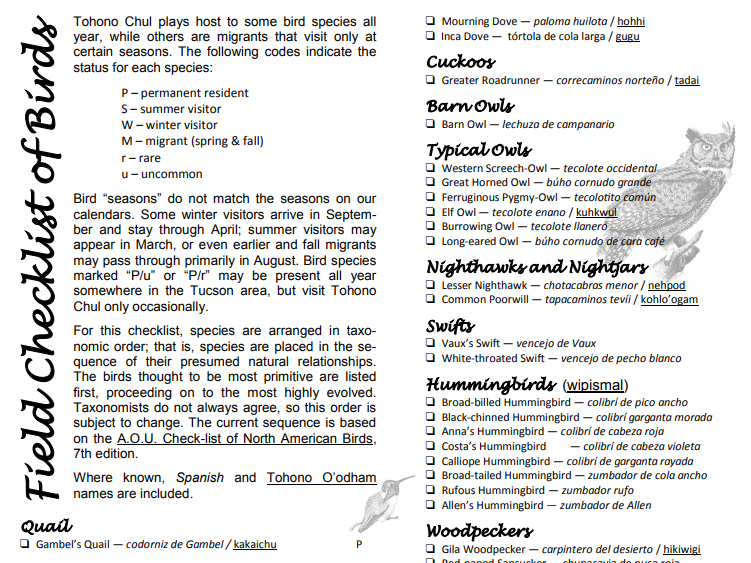

Tohono Chul Birding Checklist

Merlin Bird ID by Cornell

For Fun

Tucson Audubon Society Hummingbird Live Cam

Bird E-Books at Pima County Public Library

Day 2 – Backyard Learning & Fun

Bringing Birds To Your Backyard

Creating a Wildlife Habitat Garden

In creating any habitat garden, there are four basic components: Water, Food, Shelter, and Places to Raise Young. It is essential to possess some knowledge of these components and their importance to attracting, feeding, offering shelter and nesting opportunities for a diverse assortment of living creatures. The following offerings are methods to attract and keep wildlife along with some personal experiences in creating an enjoyable habitat for wildlife and humans.

Fun At-Home Bird Projects

From bird seed to bird feet, there are exciting science projects you can do with students of all ages to encourage interest in birds. Keeping a few key tips in mind, your summer bird watching may also help build your student’s science skills and reinforce important observation and recordkeeping skills. Add a creative angle to summer bird watching with a display board project to share at school or hang up as a reminder of a summer of birds!

Native Plants for Habitat at Home

Thanks to the Tucson Audubon Society for providing such a great list on their website of all the native plants you can add to your backyard to attract all sorts of Sonoran Desert birds! You can make a difference! Native plants provide the resources and habitat structure birds are looking for. They provide food, shelter and nesting opportunities. Learn all the little ways you can help support a happy and healthy avian eco-system, and enjoy watching them too.

Inside Birding Series

Size and Shape

Color Pattern

Habitat

Behavior

Listening To The Call

Bird Academy

Songbirds learn their songs and perform them using a specialized voice box called a syrinx. Vocally, they’re in a league of their own. These adaptations have been remarkably successful—songbirds make up almost half of the world’s 10,000 bird species including warblers, thrushes, and sparrows. The vast majority of non-songbird species make simpler sounds that are instinctual rather than learned.

Bird Song Opera

ShakeUp Music recomposed Mozart’s Magic Flute ‚Papageno/Papagena Duet‘ into an audiovisual bird song aria. Listen to an audiovisual twitterstorm performed by our feathered fellows. ShakeUp Music recomposed the Magic Flute “Papageno/Papagena“ Duet into a colorful Mozart bird aria. Listen to an audiovisual Twitterstorm performed by our feathered fellows. Keep the birds on singing – like and share the clip.

Birding Organizations

Tucson Audubon Society

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Avibase – The World Bird Database

Day 3 – Artistic Expression

Birds were the muse for this week’s coloring page downloads!

One Hundred Museums Transformed Their Collections Into Free Coloring Pages

Get To Know The Artists

Robin Westenhiser

The Night Owl

What drew Robin Westenhiser to Tucson has kept her here over 40 years. The colors, the dance of light and shadow, a time when the light seems to lavish each object of its desires and turns the ordinary into something sacred.

More

Her favorite time of day is always when the clouds turn pink. Robin works from her home in Tucson, Arizona with a beautiful view of the Santa Catalina Mountains. She is a collector of things and finds inspiration in her colorful southwestern surroundings, the Sonoran Desert, the mountains that surround the city and our big blue sky. Robin’s close proximity to the border has developed a deep love of Mexico, the colors, the foods, the traditions and the people. She loves to paint in bright colors that make her happy and feel alive! Robin’s paintings make her smile and she hopes they make others smile too!

To learn more about Robin Westenhiser go to https://www.naturaltucson.com/2018/11/01/230981/robin-westenhiser-enriching-life-with-color

Farrady Newsome

Agave Bird

“This large, glazed terra cotta bird gazes upwards towards the sky in a reflective state. The drift imagery that cloaks it speaks to the unseen current of time, especially biological time and the dangers inherent within its flow.

More

The watch, pelvis, shells and eggs can be seen to represent biological time and fertility, whereas the spiny agaves, shark tooth and poisonous datura seed represent potential dangers. This sculpture is part of an ongoing series that explores these ideas by means of a painterly glazed surface.”

Dan Weisz

Bedazzled Feathers

“The Sonoran Desert hosts more varieties of hummingbirds than any other region of the United States. One of the more stunning hummingbirds is the male Broad-billed Hummingbird, only in the deserts of Southeastern Arizona,

More

commonly in the summer. The male Broad-billed has a bright red/orange beak, a dark green body and a brilliant blue neck that takes one’s breath away.” I am a native Tucsonan who grew up in a house west of Alvernon, near Speedway when Speedway was unpaved east of Country Club. I remember playing with lizards and ants in the yard and building forts made of tumbleweeds. To me, Tucson has always been the sounds of doves waking me in the morning, the smell of a summer rain, the mountains and desert, the beauty of our sunsets and the equally mesmerizing sight of our fleeting sunrises. I love Tucson for its rich diversity of people, cultures, and traditions. After a career in Public Education, I retired and am able to spend more time outdoors. I took up photography and I now volunteer at the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum with their renowned Raptor Free Flight program, both as a narrator and as a bird handler. The Sierra Club’s “Daily Ray of Hope” has featured numerous images of mine on their e-newsletter and social networks. Tucson Audubon Society has used my work and images in their web blog, in the Vermilion Flycatcher newsletter and for various communications including print, e-mail newsletters and social networks. I have images on permanent display at Agua Caliente Park’s Ranch House and at the Paton Center for Hummingbirds in Patagonia.

To learn more about Dan Weisz go to https://www.flickr.com/photos/122902197@N03/

Jerry Cagle

Pilgrim’s Rest Return to Roost

“Birds enliven our hearts. Spirit-like beings of, and yet not of, this world. They can, at will, slip the bonds of “earthly existence” and ascend into the ethers. Watching them soar, boundless and carefree, we long to commune with them in their natural

More

milieu.” Note: The sandhill cranes in these images are wild birds that overwinter in Cochise County at the Whitewater Draw Wildlife Area in the southeast corner of the state. I encourage all to take the time to make the trip out to Whitewater Draw to observe firsthand these amazing animals in their seasonal environment.

[expand title=”MORE ARTISTS” rel=”fiction”]

Linda Ekstrum

Kindness of Ravens

“These two Common Ravens (Corvus corax), looked rather regal as they perched on this gate that sits along Highway 181, a road that skirts the Chiricahua Mountains in Southeast Arizona, while seemingly enjoying the expanse of their kingdom at the end

More

of a day. In all likelihood they are a monogamous mated pair. Note: the title of this photo is a protest against the Collective Noun designation for Ravens, that is, ‘An Unkindness of Ravens,’ which is a rather harsh judgment for a bird known for their intelligence and in some cultures been revered as Gods.”

Lawrence Beck

Full Reverse

“To my way of thinking Hummingbirds represent the essence of flight. Their ability to hover, fly inverted and in reverse is unequalled in the Avian kingdom. That they exist only in the Americas and are the smallest of all birds adds to their

More

unique aspect. I’ve chosen to study and photograph Hummingbirds for the past nine years, following my first exposure to them in 2006. Rather than follow the current norm of using between six and twelve flash units mounted on light stands placed 18” from a flower or feeder I prefer to photograph them from a distance of 15-20 feet, with a super telephoto lens (840mm equivalent), tripod and single flash mounted to a ring attached to the lens foot. Flash is used at the lowest power setting so as to provide fill light and not overwhelm the bird with a blinding intensity of light that would require ‘glare recovery’ endangering the bird’s vision. With this technique I can capture wing movement rather than freeze all motion, rendering the bird lifeless as multi flash technique often does. Wing movement represents life. With enough time and exposure to the same birds relationships are developed. Food can be a powerful motivating force, especially when the Broad-billed Hummingbird consumes up to three times its body weight in nectar daily. They are aware as to where their food comes from and can be very trusting. I’ve had up to three hummingbirds land on me while cleaning and refilling their feeders and have had two Annas fly between my legs while I was leaning forward photographing Calla Lilies… emitting what sounded like a giggle as they flew away. For over 30 years I’ve endeavored to find a way to present my work in unconventional ways. This past summer I developed a means of presenting my work in a mixed media format with no frame and no glazing, allowing the delicate texture of the substrate to complement the image.”

Brian Hooker

Last Face

“The barn owl is a nocturnal predator whose wide range includes a year-round presence in much of Arizona. With a feathered dish-shaped face and slightly offset ears, the barn owl has the ability to detect and to locate prey from their slightest sounds. Sharp talons and a hooked bill quickly snatch and dispatch small mammals. The barn owl’s call is a long hissing shriek, rather than a hoot often associated with owls. One can imagine that as the barn owl descends, the prey takes a quick glance backwards at the last face it will ever see.”

[/expand]

Day 4 – Art In Nature

A conversation with avid birder/photographer Dan Weisz and James Schaub, Tohono Chul Curator of Exhibitions

A Hunting Vermilion Flycatcher (left)

A Barn Owl Turning in Flight (top)

Dessert in the Desert (top)

Bedazzled Feathers (right)

Maybe it is movement. Maybe it is color. Maybe it is sound. Maybe it is a feeling in the air. Whatever it is, there is something that made you stop and look. Whatever it is, it is beyond just the visual. Whatever it is, it needs to be experienced.

I have spoken with many birders over the past five years at Tohono Chul about what it is that drives them. They come from widely divergent backgrounds yet they share an incredible, almost ritualistic fascination with the chance to glimpse, for just a moment, the many feathered mysteries of the natural world.

Read More

They seek to find something they haven’t seen before.

Just as birders are finely tuned to their surroundings so too is the artist. Knowledge, patience, and a heightening of all of the senses is required for imaginative and informative discoveries in both fields. The parallels are uncanny.Tucson based photographer Dan Weisz bridges the two fields.

James Schaub: Dan – what is your background? What brought you to photography? What brought you to birds?

Dan Weisz: I grew up in Tucson and have always enjoyed the beauty of the desert: our sunsets, the big blue sky, the variable colors of the mountains, and the special beauty of all of the plants and living creatures around us. In my twenties, I met a friend who was a birder and he took me along with him on a number of birding adventures. That got me started.

JS: So many times, when I see a photograph that grabs me, I imagine the photographer trekking to a super remote place to get the shot – to find the subject. Often times I am told it was taken in the backyard or just off the roadside. It doesn’t make the image less romantic for me – it just hammers the point home of how you need to be there to capture that image. It doesn’t matter where – you just need to be there. How do you get “There”? How do you determine what place to go, what place to be.

DW: As you say, “there” can be anywhere. Some of my favorite photos came from my back or front porch or the neighborhood. But there are many places to wander in Tucson and southern Arizona (and beyond). I think that two ways to express this: The old cliché “stop and smell the roses” is one way to think about finding the good and the interesting in the world around us. Another old saying “Be here now” implies the same thing. For me at least, I am generally not driven to go and “get” a photograph; I just go out hoping to see something that interests me. Birding and photography are flexible – there is an art to each. They encourage you to explore the world and help you to treasure each moment.

JS: Do you have any favorite places in and around Tucson and Southern Arizona? Any spots you return to over and over?

DW: You mean besides Tohono Chul? There are a number of city, county and state parks that I visit, and places like Sabino Canyon, Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson Audubon’s Paton Center for Hummingbirds in Patagonia, Madera Canyon, and the agricultural areas north of Marana are just a few that I enjoy. Also, if I see something special then I will return to a spot over and over again. Right now I’ve been visiting several mid-town nests of Great Horned Owls every other day. I begin that circuit every spring as breeding season begins.

JS: What make them special?

DW: Each one of those places attract a wide variety of birds, animals, and insects through the rich diversity of habitat at each site. The flora and fauna varies depending on the time of year, so there is both the opportunity of seeing something seasonally “new” along with seeing “old friends” again. And every place you go has its own characteristics and vibe.

JS: Once you are in the place. What is your sensory response to the stimuli you experience – what grabs you first?

DW: This goes back to “Be here now” or “stopping to smell the roses”. Just be present and look around. There may be sounds, smells, movement or something visual that grabs my attention. Often, I’ll be looking for something particular but then get interrupted by something different but interesting that happens along. It’s a matter of just wandering in an area and being conscious of the world around you.

JS: Are the places/habitats connected to a particular kind of bird? Is there a bird that you always wanted to see that finally appeared? Is there one that has proven elusive?

DW: Some birds need a very specific habitat. Some are more of a generalist where they live. So if you want to see ducks, you need to find some water. If you want to see a Vermilion Flycatcher, find any local field or open space. Southern Arizona is a unique place to find birds and people travel here from around the world for the opportunity to see our specialties. The Sky Islands are a bridge between the northern tip of the Sierra Madres and the Rocky Mountains and, surrounded by different deserts, offer an incredible range of biological diversity. Sometimes I’ll go looking for specific birds and hope to see them, but I don’t chase rarities. I am more of a generalist and, like my children, I do not have any favorites!! I can be surprised with the most common bird’s beauty or behaviors, so I am easy to please.

JS: Do you log the birds you see? – What goes into that?

DW: I do not usually create lists. There are so many different birders and bird watchers. Some people are actively listing the birds they see- lifetime, by year, by state, by location. Others do not do that and just spend their time observing the birds. Everyone finds what works for them and their own personality and goals.

JS: Talking before about bridging the fields of avid Birding and making Art – how do you feel they run parallel – or are they closer than I thought? Do they intersect? Both rely on observation and reaction.

DW: Mother Nature is the original artist and the incredible amount of beauty she provides is overwhelming. In birding, you are out in nature and encouraged to explore the world around you. That may just be looking out your kitchen window, or it may entail going on a trek. Wherever you are the complexity and beauty of nature is never-ending. When I retired I decided to try doing more birding and I thought I’d pursue my interest in photography. As I began to capture beauty through my photographs, it caused me to become even more interested in what I was seeing. It is both instinctual- I know when I see something interesting or something that looks beautiful. And being able to capture that sense of beauty is the challenge of photography.

JS: Does the image work for you as “document” or as “art”? Can they work together, can they be one and the same?

DW: I’m not sure I think of it either way or perhaps the image works as both together. For me, I enjoy seeing if what I captured with my camera helps to elicit the wonder I saw in the field. At times, it reveals details and nuances that I missed at the time in the field but the camera captured the “in the moment”.

JS: What kind of gear do you work with – binoculars – camera – computer ?

DW: My camera is with me always. I have a Nikon D500 and the lens I use most often in the field is a zoom lens, 70-300mm. I use a bigger zoom at times and smaller lenses as well depending on the situation. I often will carry binoculars. When I get home I will process the photographs using Lightroom, a popular Adobe application.

JS: How much of the image do you do “in camera”? How much in an editing program? Which one do you use?

DW: I learn very slowly, but the ideal is to compose the picture before you take it. I hope I am getting better at it. I try to be aware of where the subject is, what the lighting is and where it is coming from, what the background is and what type of behavior I want to see or want to wait to capture. If I do all of these well, and have the proper camera settings and even focus on the subject well, then most of the work is done. When I get home I will process the photographs using the application Lightroom. I once had a friend derisively dismiss one of my photos because she was sure a bird couldn’t look “that pretty”. She “accused” me of Photoshopping it. My response was that I did nothing more than I did to myself every morning before leaving home. Washing my face, brushing my hair, shaving and putting on a smile didn’t change who I am. It just brings out my natural self. That’s what is done in editing a photo- bringing out the best of what you already captured when you took the photo.

JS: Does the camera ever get in the way – or is it part of you?

DW: I am now more comfortable with myself as a photographer so the camera has become a more natural part of me. But it can always get in the way. I’m only human you know. Sometimes I just bird and photography is not my goal. And there are times when I am only interested in watching the bird (or I know it is a situation where I could take any decent photo). But if I have my camera, I am always ready to shoot what I may find along the way.

JS: Long before we started to work with you , your name would come up almost on a weekly basis. Our wonderful docents and volunteers were not only privy to images, and your notes about them – they knew your personally as a thoughtful guy with a keen eye and a camera, intensely interested in finding that unique subject, and sharing your thoughts on the experience of getting “there”, being “there”, and being in the moment.

Can you share the process and the vehicle of posting your photography online? How did you start doing it? Who do you reach – what is the response and how do you respond to it?

DW: When I first began taking pictures after retirement I began sharing them with my family. That was fun. But I found that my family wasn’t quite as enamored of birds and nature as I was, so I began adding commentary to my photos in order to help to grab their attention. As time went on, I added friends and acquaintances to my photo email list and it continued to grow and grow. I know that many of the people on my list enjoy my work so much that they forward it to their friends and family. That brings me very much pleasure. Those ‘ripples in the pond” as people pass my photos on are a wonderful affirmation that my photos speak to people. I continue to develop both my photography skills and my storytelling skills as I strive to make what I share more attractive to my ‘audience’. In addition, I post photos on social media and several Facebook pages, in a flickr account, and on our neighborhood HOA webpage which I share with a large region of the city through Nextdoor. I am grateful that Tucson Audubon has used my photos in their media as has the Sierra Club through their Daily Ray of Hope. Tohono Chul used one of my Screech Owlet photos for their guides last year and having photos as part of two different recent exhibits in the Main Gallery of Tohono Chul was very exciting.

JS: Where can we see more of your work?

DW: My photos are available in my flickr site at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/122902197@N03/albums

and

My BirdsoftheDesert site on Etsy is at https://www.etsy.com/shop/birdsofthedesert

My HOA wildlife page, with many of the photo emails is at http://wildlife.foothillsclusters.com

I can be reached at dan@Weisz.org

JS: Dan, is there a birder’s bucket list? Do you have one?

DW: I went to a lecture by a renowned photographer once. He said that one of the questions he is asked wherever he speaks is “How many lenses do you need?” And he said the answer is “Just one more”. Each birder and each photographer has a list, formal or informal, of the “one more” bird or photograph he or she wishes to capture. That’s part of what keeps us going.

JS: So true. Thank you so much for your time and expertise Dan. I look forward to working with you on future projects here at Tohono Chul.

DW: You’re welcome and thanks James!! Tell me what bird you see out your office window. What does it look like and what is it doing?

JS: Well, I think it is the same Cooper’s hawk that flew over me when I pulled in this morning. Right now he is up high in that big mesquite tree outside the Exhibit House – just waiting for things to move. Like all of us, I guess.

DAN WEISZ biography

“I am a native Tucsonan who grew up in a house west of Alvernon, near Speedway when Speedway was unpaved east of Country Club. I remember playing with lizards and ants in the yard and building forts made of tumbleweeds. To me, Tucson has always been the sounds of doves waking me in the morning, the smell of a summer rain, the mountains and desert, the beauty of our sunsets and the equally mesmerizing sight of our fleeting sunrises. I love Tucson for its rich diversity of people, cultures, and traditions.

After a career in Public Education, I retired and am able to spend more time outdoors. I took up photography and I now volunteer at the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum with their renowned Raptor Free Flight program, both as a narrator and as a bird handler.

The Sierra Club’s “Daily Ray of Hope” has featured numerous images of mine on their e-newsletter and social networks. Tucson Audubon Society has used my work and images in their web blog, in the Vermilion Flycatcher newsletter and for various communications including print, e-mail newsletters and social networks. I have images on permanent display at Agua Caliente Park’s Ranch House and at the Paton Center for Hummingbirds in Patagonia.”

Dan Weisz has been featured in the TOHONO CHUL exhibitions Día De Los Muertos (2019) and ON THE DESERT | the Discovery and Invention of Color (2020)

Artists and Exhibits

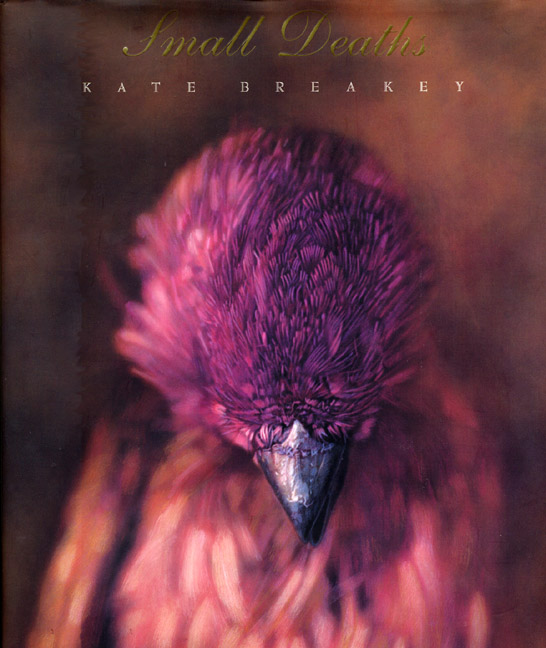

Kate Breakey – Small Deaths Series

Small lives end every day—the unfledged bird fallen from its nest, the unwary lizard caught by a cat—as unnoticed in dying as they were living. Deeply moved by these small deaths since her childhood in South Australia, photographer-artist Kate Breakey has been photographing found animal remains since the mid-1990s, creating stunning, oversized, hand-colored images that—paradoxically—glow with life.

This volume is the first book-length work devoted to the photographs of Kate Breakey. It gathers color images from her ongoing “Small Deaths” series. These birds, flowers, lizards, and insects vividly express Breakey’s desire to preserve each lost creature—to “freeze it in time, suspend it in space, immortalize it so that its beauty and its death are memorialized.” In a brief afterword, Breakey traces the origins of her art to a childhood spent among domestic and rescued animals on the Australian coast. In the introduction, noted art critic A. D. Coleman links Breakey’s work to the larger traditions of still-life painting and the postmortem photography of the nineteenth century.

Remains of the Day, Kate Breakey finds monumental beauty in ‘Small Deaths.’ – Review by the Tucson Weekly – Full article here

Purchase Small Deaths Book Here

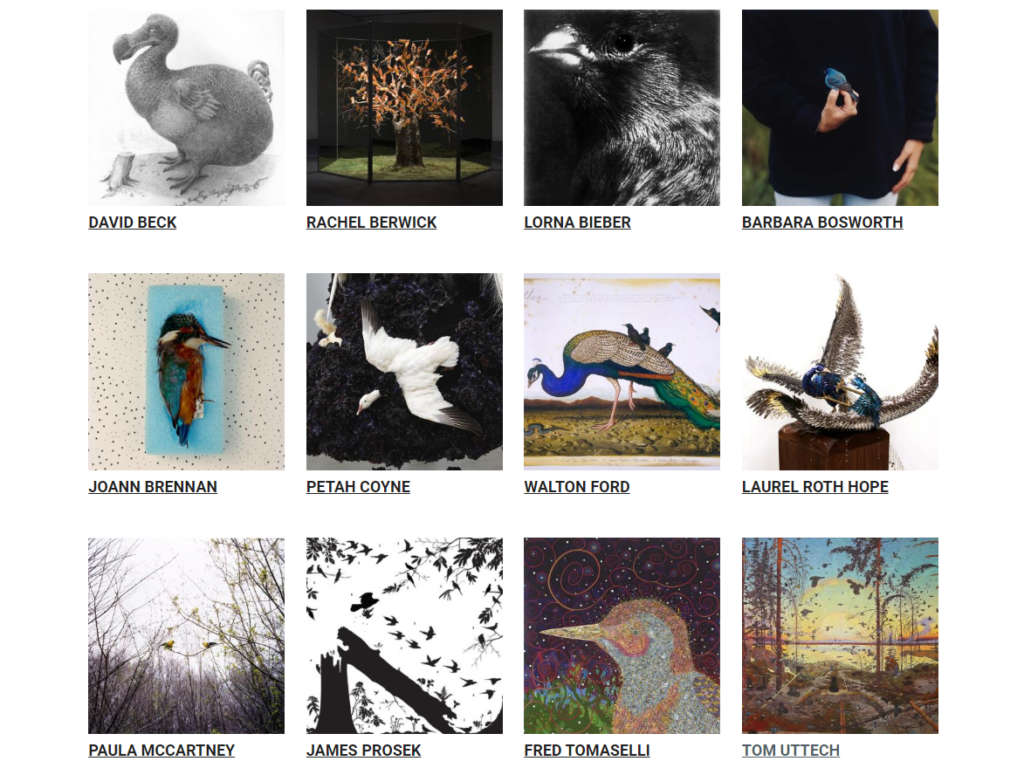

Smithsonian American Art Museum – The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art

Birds have long been a source of mystery and awe. Today, a growing desire to meaningfully connect with the natural world has fostered a resurgence of popular interest in the winged creatures that surround us daily. The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art examines mankind’s relationship to birds and the natural world through the eyes of twelve major contemporary American artists.

The presentation of “The Singing and the Silence” coincided with two significant environmental anniversaries—the extinction of the passenger pigeon in 1914 and the establishment of the Wilderness Act in 1964—events which highlight mankind’s journey from conquest of the land to conservation of it.

More

Although human activity has affected many species, birds in particular embody these competing impulses. Inspired by the confluence of these events, the exhibition explores how artists working today use avian imagery to meaningfully connect with the natural world, among other themes. While artists have historically created images of birds for the purposes of scientific inquiry, taxonomy or spiritual symbolism, the artists featured in The Singing and the Silence instead share a common interest in birds as allegories for our own earthbound existence. The 46 artworks on display consider themes such as contemporary culture’s evolving relationship with the natural world, the steady rise in environmental consciousness, and the rituals of birding. The exhibition’s title is drawn from the poem “The Bird at Dawn” by Harold Monro

View Full Exhibit Here

Walton Ford – view work

Walton Ford has been depicting animals for as long as he can remember. Although immediately reminiscent of traditional natural history painting, Ford’s images double as complex allegories, blending depictions of nature with historical events and sociopolitical commentary. Over the last twenty years, Ford has created more than one hundred paintings and prints with birds as the primary subject.

Tom Uttech – view work

Tom Uttech work is inspired by wide expanses of unspoiled wilderness in his native Wisconsin and neighboring Quetico Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada. Uttech’s paintings, which take their names from various Ojibwe words and phrases, are fantastic imaginings, often populated with hosts of birds and other animals that traverse the landscape in a flurry of natural diversity

Something You Should Know

MIGRATORY BIRD TREATY ACT of 1918 – The MBTA was passed in 1918 to combat over-hunting and poaching that supplied the enormous demand for feathers to adorn women’s hats. State-level hunting laws were not working, and bird populations were being decimated. … The MBTA applies only to migratory bird species that are native to the United States or the U.S. Territories, and that a native migratory bird species is one that is present as a result of natural biological or ecological processes. …In 1962 it was updated to address how Native American tribes can collect feathers from protected birds for religious ceremonies (a practice otherwise banned by the MBTA). …The statute makes it unlawful without a waiver to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, or sell birds listed therein as migratory birds. The statute does not discriminate between live or dead birds and also grants full protection to any bird parts including feathers, eggs, and nests.

From time to time with EXHIBITS we encounter artists that inquire about incorporating bird parts in their art: feather, eggshell, bone, or nest. In every instance, the artist has found the various parts out in nature. They are informed that bird parts cannot be exhibited because it is in violation of the MBTA. Once the MBTA is explained to them, the artists understand its significance – taking with them an awareness and knowledge that is shared within the arts community.

Behind the Scenes With the World’s

Top Feather Detective

Tucson Audubon’s Paton Center for Hummingbird’s Wildlife Pavilion / DUST

The Paton Center for the Hummingbirds, now under the care of the Tucson Audubon Society, has its roots in the deeply personal; the 1.4-acre property was originally a private residence, home to a couple, Wally and Marion Paton, who welcomed into their garden the migratory hummingbirds that sweep through the region and, eventually, the public as well.

The Hummingbird Pavilion celebrates the intimacy of these roots and their inspiration: the communion of people and wildlife who find, at least for the moment, their home here. Built with a keen attention to both the profound simplicity of that moment and to the long histories and futures that extend on either side of it, the project captures in built form the lightness of the hummingbird’s flight, both impossibly still and so quick you can hardly perceive the movement.

Day 5 – Weekend Inspiration

Bird-Inspired Boxes!

Crafty Bird – $40

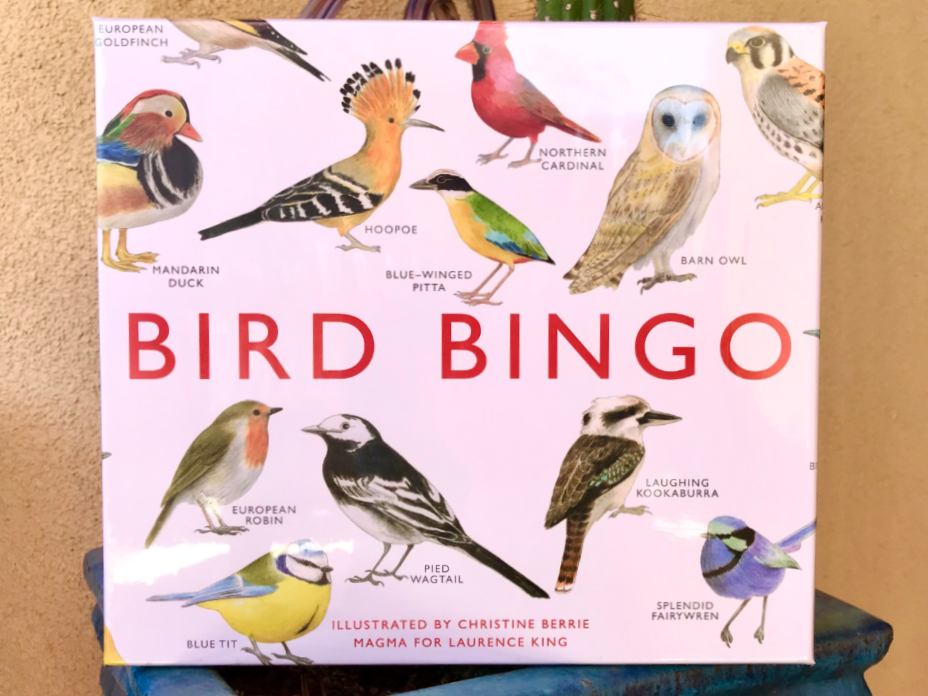

Bird Bingo – $30

Start Birding Box – $35

Indoor Bird Fun – $18

Crafty Bird

Step-by-Step Paper Mache Directions

How to Make a Little Paper Mache Bird

Birds On a Stick Craft Tutorial

Next Week’s Theme