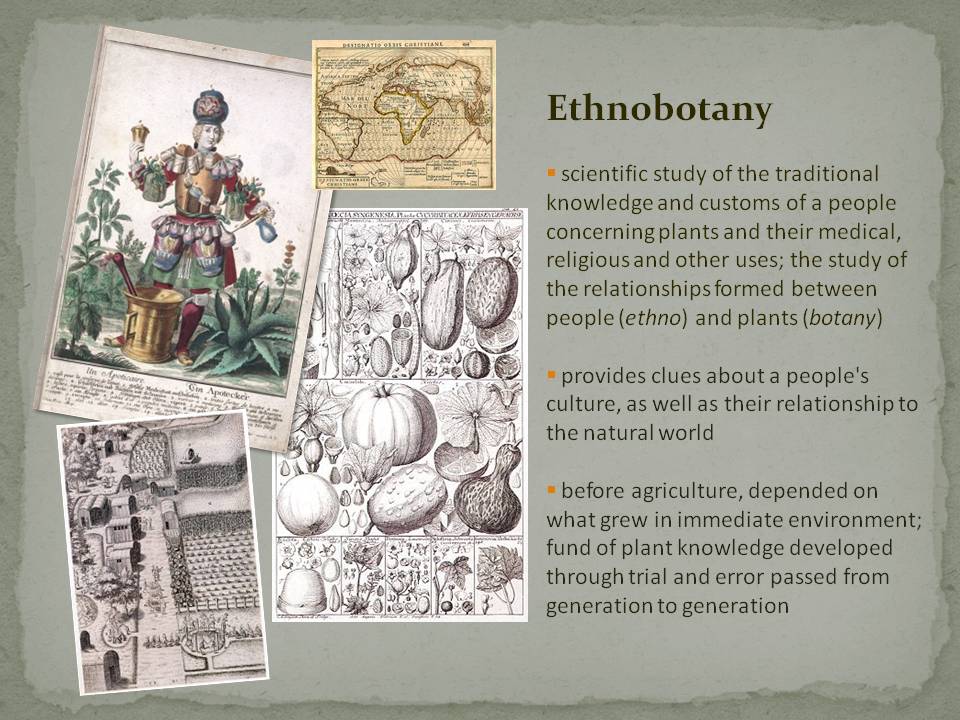

In the simplest of terms ethnobotany is the relationship between plants and people. And we can see this relationship around us all the time. Ethnobotany offers insight into our own culture and cultures around the world. Often thought of as addressing the past, the way people used to use the plants in their environment, ethnobotany is very much alive and thrives in our modern world. It shows us just how ubiquitous plants are in our lives. So whether you are using plants for food, clothing, as construction material, or just to admire the beauty and resilience of our Sonoran Desert plants – you are engaging in ethnobotany. When you are enjoying the artistry behind a Tohono O’odham basket, with contrasting light yucca fibers and dark devil’s claw fibers. Or enjoying a Sonoran desert inspired meal of mesquite crackers, nopalitos salad, I’itoi onions, and stewed tepary beans seasoned with spicy chiltepin, you are practicing ethnobotany.Join us this week to explore our world through an ethnobotanical lens and witness how plants nourish our bodies and souls.

As we explore ethnobotany together this week. Feel free to share what you do with marketing@tohonochul.org or sspikes@tohonochul.org. Volunteers and docents, you can share to our Tohono Chul Volunteers and Docents Facebook group directly too!

Day 1 – Sonoran Desert Survival

“We hope these sketches will encourage arid-land dwellers to feel more at home with the desert’s bounty, a richness that cannot be understood simply in utilitarian terms. Even if you never get eat a carob-like mesquite pod or treat a cold with creosote leaf tea, these plants have something to offer. It may be just the music heard when standing beneath a spring-flowering mesquite canopy, alive with five thousand solitary bees, of the smell of a creosote bush releasing fifty volatile oils to the ozone-charged air during a summer storm. Even if you don’t gather the desert, let it gather a feeling in you. Even if you don’t swallow it as medicine, meditate upon it: the desert can cure.”

from Gathering the Desert by Gary Nabhan

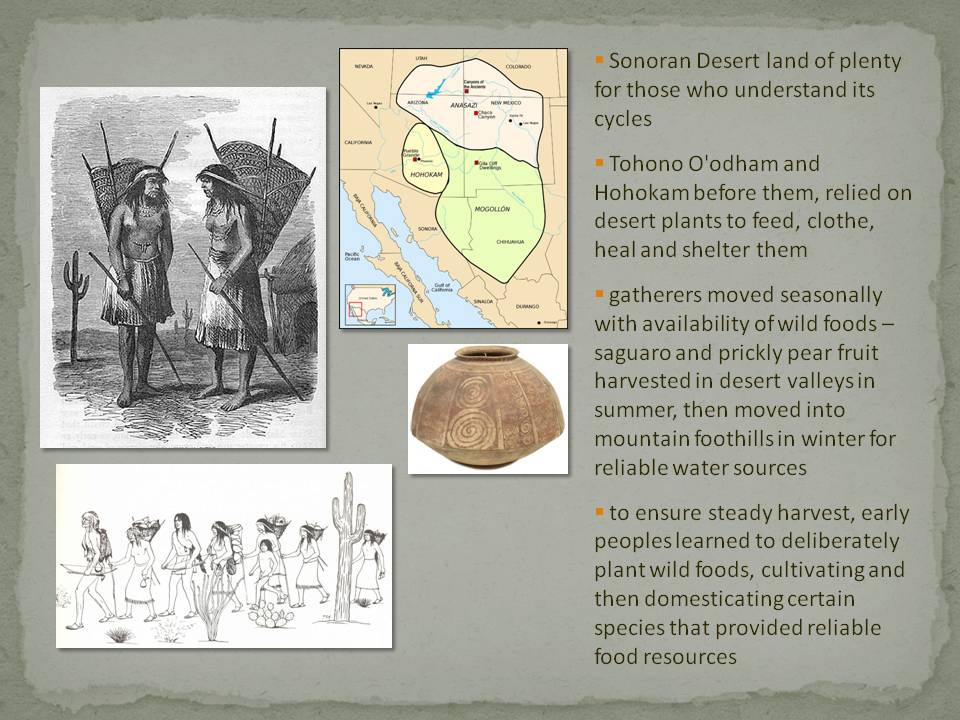

The Tohono O’odham and the Spanish foraged and flood-farmed this land for many years. The Ethnobotanical Garden displays the types of plants they used for food, basket making, medicine, and cultural ceremonies. The summer garden features native plants flood farmed by the Tohono O’odham, as well as indigenous plants they harvested for their fruit, seeds and fibers. The winter crop features plants the Spanish and other Europeans brought with them to the New World. These crops helped to bring the Tohono O’odham to the missions to live, because they were a guaranteed food source during the time of year that food was scarce.

The Sonoran Desert Native Food System

Tohono O’odham Food System

Harvesting Cholla Buds

Harvesting Mesquite Pods

Our Cultures Are Our Source of Health

Prickly Pear Fruit & Pads

Velvet Mesquite Pods/Seeds

Desert Harvesters

Desert Harvesters is a nonprofit, grassroots group that promotes the harvest of native, wild, and cultivated desert foods and also advocates for the planting of indigenous, food-bearing shade trees (such as the Velvet mesquite) within rainwater harvesting “gardens” (in home landscapes and public rights-of-way).

Preserving Historical Edible Landscapes

I am a citizen of the border, born and raised in the Sonoran Desert. My hometown is Magdalena, Sonora, Mexico, a historic community sixty miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border and the twin cities of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. Now I reside in Tucson, Arizona, sixty miles inside the

Wonders of the West

On this segment of “Wonders of the West” they head to Tohono Chul for a tour and a taste of the desert.

A Trail Dust Town Making Headlines

Tucson: City of Gastronomy

On 15 December 2015, Tucson, Arizona, became the first UNESCO City of Gastronomy designated in the United States, joining the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN). Currently comprised of 180 cities in 72 countries, the UCCN is an association of urban areas around the world with objectives that emphasize strengthening international cooperation between cities.

Tucson Becomes an Unlikely Food Star

here are food deserts, those urban neighborhoods where finding healthful food is nearly impossible, and then there is Tucson. When the rain comes down hard on a hot summer afternoon here, locals start acting like Cindy Lou Who on Christmas morning. They turn their faces to the sky and celebrate with prickly pear margaritas. When you get only 12 inches of rain a year, every drop matters.

Tucson, First Capital of Gastronomy

Every day, tens of thousands of cars barrel down Interstate 10, a highway that hugs the western edge of Tucson, Arizona. Many of these drivers may not realize that they are driving past a region with one of the longest food heritages on the continent. Often considered the birthplace of Tucson itself, this swath of Sonoran Desert nestled at the base of the Tucson Mountains is where the

Making Food Connections

A blog by Jo Falls – Director of Education

In one sense, it was a perfect storm.

The First Element

In fall 1992, I was prepping for my second docent class, having taken over the Education Department the year before. One of the subjects that was especially intriguing to me was Ethnobotany. People and plants, the synergy of life in the Sonoran Desert. I was determined to make the topic more relevant and less of a curiosity to these future desert interpreters. If they were going to interact with the public and describe a saguaro harvest or the culinary uses of mesquite, then shouldn’t they have participated in a harvest or tasted mesquite meal?

READ MORE

I don’t recall where I came by the small bag of mesquite flour, but my plan was to make something authentic, the kind of baked mesquite cake that the Hohokam might have eaten. Right. The dry, hard, unleavened lump somewhat resembling a petrified cow flop was not well received. I would have to rethink this if I was going to inspire my students and make the food plants of the desert accessible.

The Second Element

I was inspired to new culinary experimentation by “Great Chefs of the Southwest” which had aired on PBS just a few years before. It had turned many of us into wannabe chefs. Heck, one of those chefs, Donna Nordin was the vision behind the menu at the Tohono Chul Tea Room, being managed at the time by famed Café Terra Cotta!

The Third Element

I met Carlos Nagel, a man with a mission. Concerned by the loss of mesquite forests throughout northern Sonora, Nagel sought to demonstrate that the sustainable harvesting of seed pods, rather than the destructive cutting of trees for firewood and charcoal, could slow the conversion of forests to empty rangeland and increase income for rural communities. Like Gary Nabhan (Gathering the Desert) and others, he also believed that mesquite could be one of the world’s most important food sources; he just had to convince the FDA. While working on improving quality controls to meet FDA standards, he was looking for guinea pigs to experiment with different source batches of flour (some came from South America) and different ways to use it in recipes. Guess who volunteered!

First Steps

With the help of a small cadre of like-minded, food-centric docents, including several who had suffered through that first mesquite loaf, we developed a once-monthly specialty tour of the grounds – A Taste of the Desert – designed to introduce guests to the edible and useful plants of the Sonoran Desert. We taught ourselves to harvest cholla buds and dry them and juice prickly pear fruit. We even tackled prepping prickly pear pads – nopales – one thing I admit now I don’t mind anyone using from a jar.

From there, it was an outreach program for local schools complete with show-and-tell items like dried cholla buds, tepary beans and chiltepines in a saguaro rib “medicine” chest made by Lee Mason and food samples – jarred nopalitos, prickly pear candies from Cheri’s Desert Harvest and mesquite cookies made from one of Nagel’s experimental recipes. And for adults, a speakers’ bureau slide presentation for that covered the A (agave), B (barrel cactus) and Cs (chollas) of edible and useful plants. The most fun of all was that I started cooking for the docent class, on “Ethno” day, serving them a lunch of desert foodstuffs and giving them the recipes to take home and try themselves. I wanted students to share these foods with family and friends, spreading the word, increasing familiarity and demand. If anyone wasn’t up for harvesting and prepping their own ingredients, it didn’t matter. Go ahead and buy the prickly pear syrup or the nopalitos in the jar, the important thing was to use them.

Accepting the Challenge

The elements had come together and it was time to embrace the epicurean possibilities of desert edibles, involving more people in the experiment. It was the new millennium, and we had begun hosting small groups for a more elaborate “Taste of the Desert,” tours and slides followed by Sonoran cookie samplers, heavy hors d’oeuvres or even full meals. We were pate-ing tepary beans, pickling cholla buds and mixing up chili and posole. The Harvard Club loved the food, the seniors bus tour from Poughkeepsie, not so much.

An inveterate reader of cookbooks, I pondered what more we could do with these ingredients and other native foods of the New World. Prior to this time, there weren’t a lot of cookbooks that took a nouvelle cuisine approach to native foods (now there are a number of really good ones). Mostly they recycle traditional recipes. As I have been quoted as saying, “I never met a recipe I didn’t try to change.”

As an excuse to experiment and as fundraisers for Tohono Chul, I offered private dinners in 2001, 2007 and 2012, trying so see just how far I could push the envelope. Smoked salmon blue corn crepe quesadillas or fried green tomatillos with corn pudding and achiote rabbit were on the menu one year. Three sisters (corn, squash, beans) soup shooters, duck breast cassoulet with tepary beans and buffalo steak with warm sweet potato salad were part of the twelve-course tasting menu another.

I almost threw in the apron after that last one, but no, I still had to try making that mesquite crust, bittersweet chocolate tart with crème anglaise.

Making the Connection

In an essay on The Pleasures of Eating, Wendell Berry feared that for many, food was an abstract idea not much considered until plucked from the grocery shelf. Instead, he implored us to build an acquaintance with our food by learning its backstory, sourcing it locally, cooking it and even growing it ourselves.

The point is, “food is our common ground, a universal experience,” according to James Beard. We often reaffirm our connections to society through food – a shared meal with family and friends. We celebrate our culture and our heritage through food – grandma’s secret recipe for apple strudel or the tradition of the feast of the seven fishes on Christmas Eve – in my house it was oyster stew. Living in new places gives us access to new foods, new traditions and the opportunity to be a global diner. That includes the desert’s bounty.

Day 2 – Victory Gardens Making A Comeback

Getting Started

The Original Victory Garden

Vegetable Garden – Master Gardeners

UA Cooperative Extension

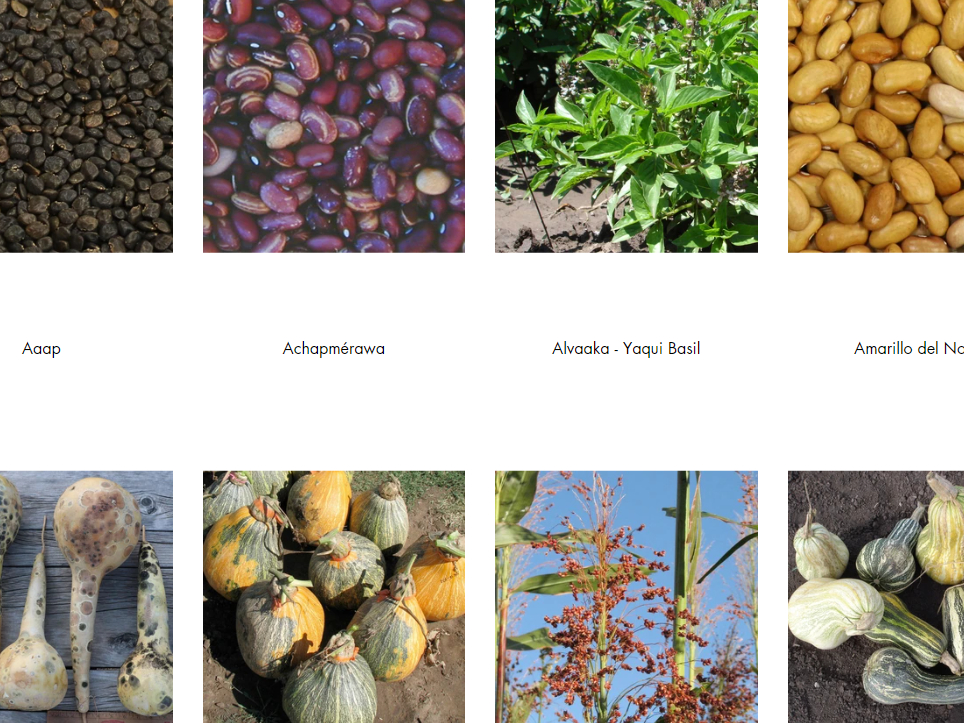

Seed Resources

Seeds of Change

Native Seeds/SEARCH

Pima County Public Library

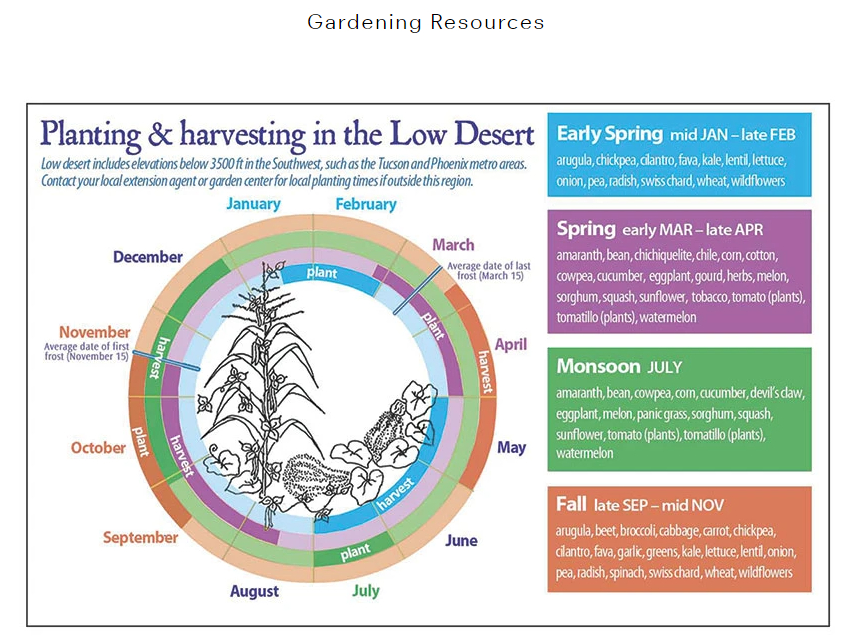

Gardening Resources

When To Garden

Pima Master Garden Program

Southwest Victory Garden

PBS – Victory Garden

Edible Communities

Day 3 -Artistic Expression

Download this week’s coloring sheets showcasing Ethno Botany

Get To Know The Artists

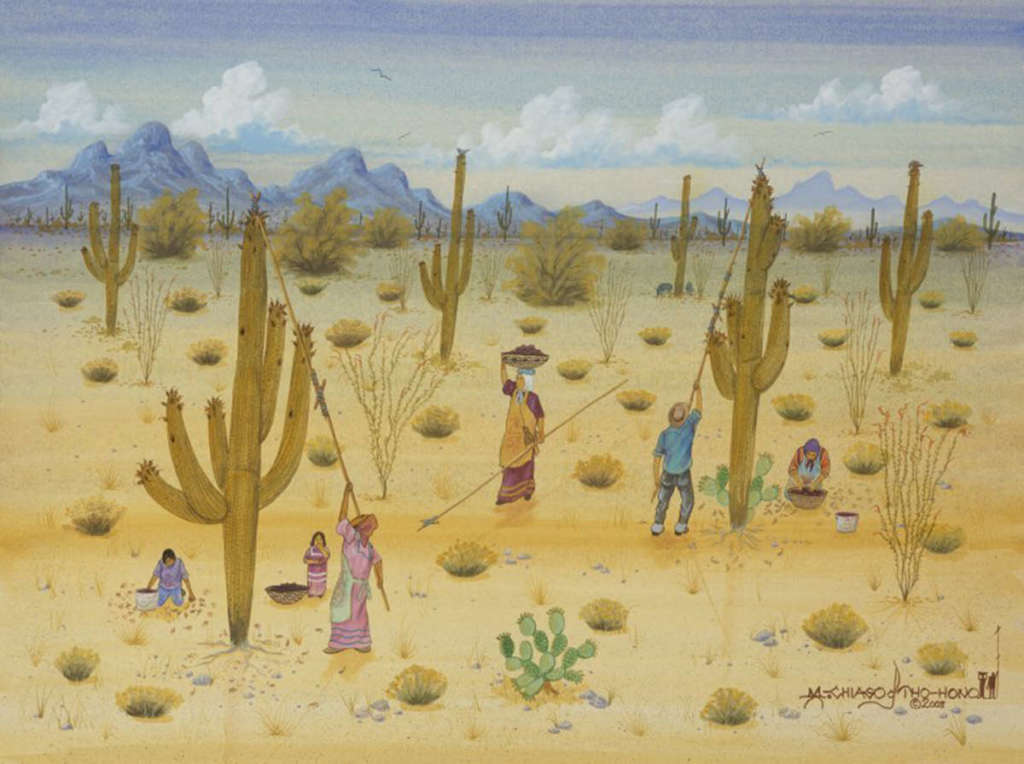

Michael Chiago

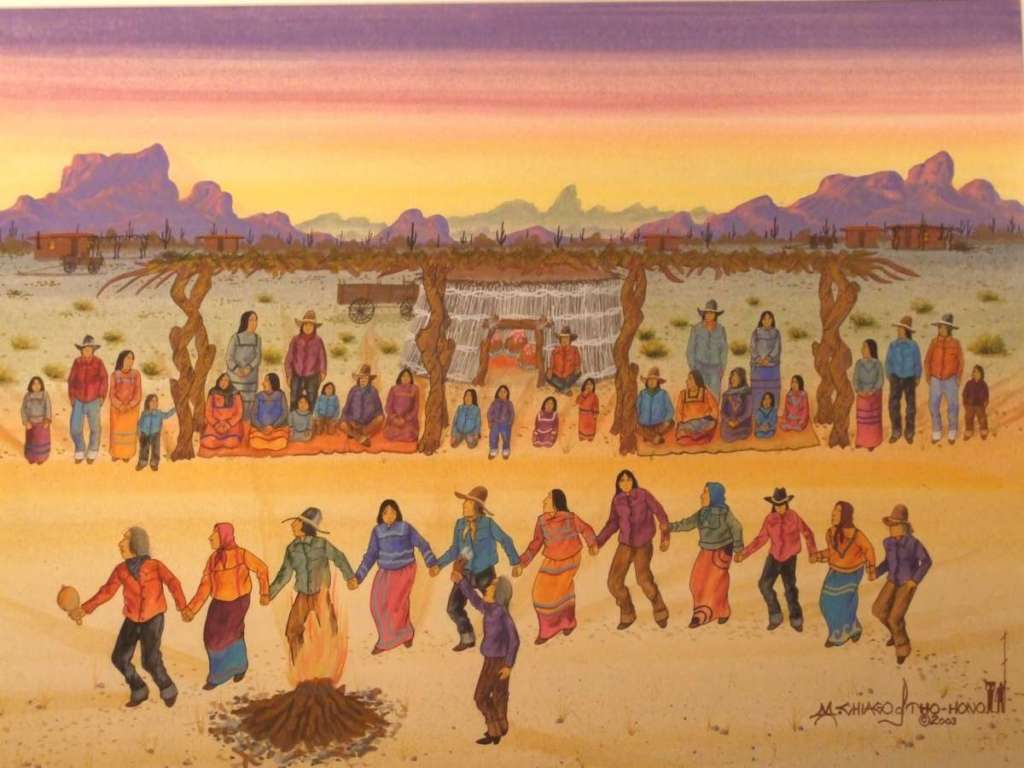

Wine Ceremony

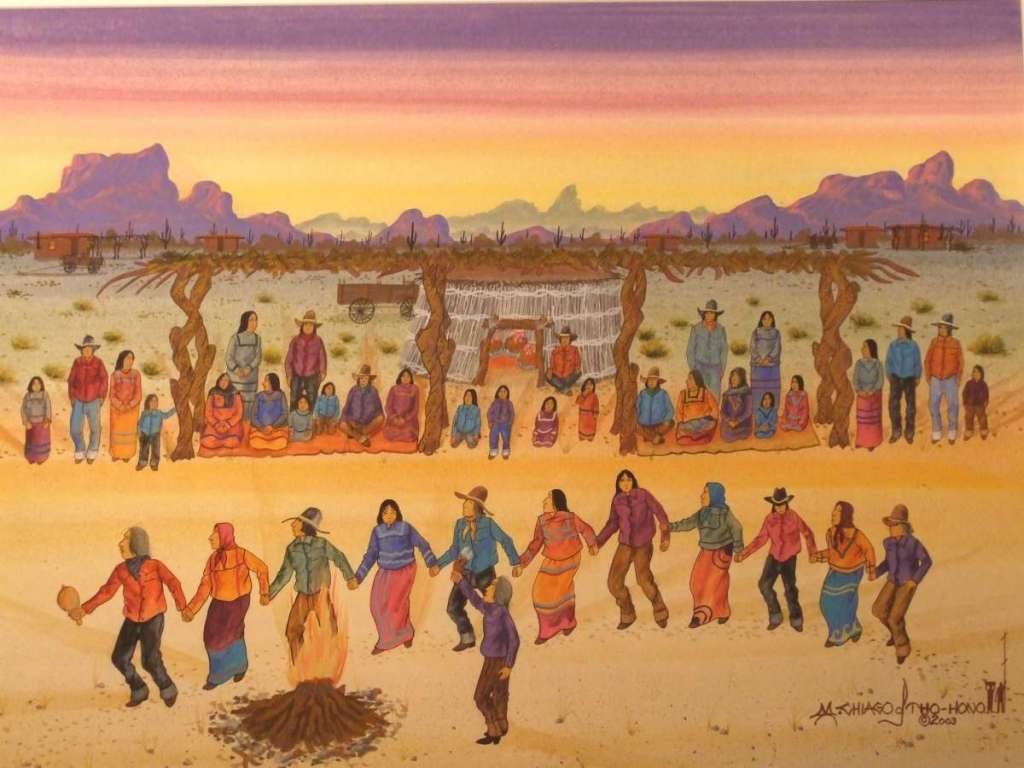

I’itoi, the creator of the Tohono O’odham, taught the Desert People their sacred wine ceremony so they could summon the rain. He taught them to make saguaro wine and gather to drink the wine and sing important songs to sing down the rain.

More

For two nights, villagers dance in a circle outside of the Rain House where the saguaro wine ferments. The chief singers sing and make music with gourd rattles. The medicine man, in the center, holds eagle feathers to catch the wind to blow the clouds in, bringing rain. Once the wine is ready, people sit in a circle and sing stories about how the wine makes the rains come and pass the wine baskets around, drinking until it is gone.

Michael Chiago was born on the Tohono O’odham reservation west of Tucson. Set against a backdrop of mountains and desert, his artworks depict the traditional gatherings that bring his people together in friendship and prayer. Chiago illustrated the children’s book, Sing Down the Rain, which tells the story of the saguaro wine ceremony. These paintings are part of a series commissioned by Tohono Chul for our Saguaro Discovery Trail that explores the importance of the saguaro for the Tohono O’odham people.

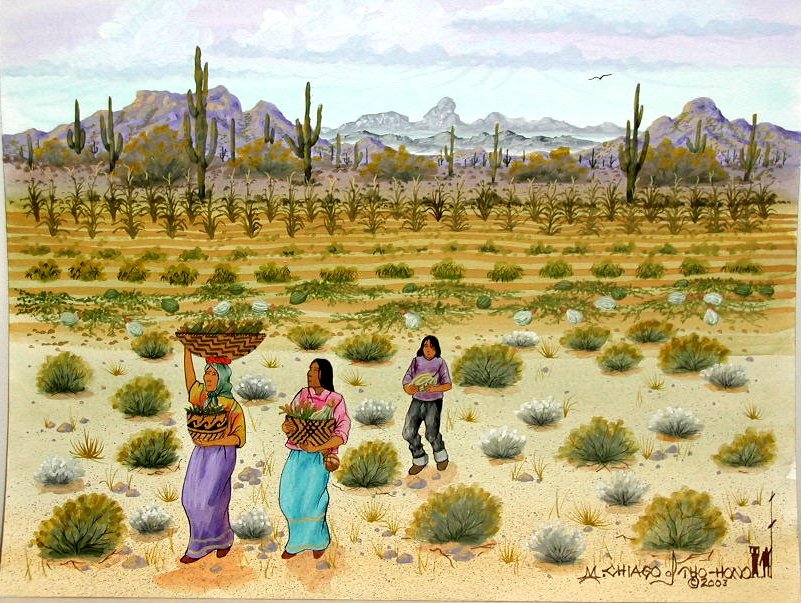

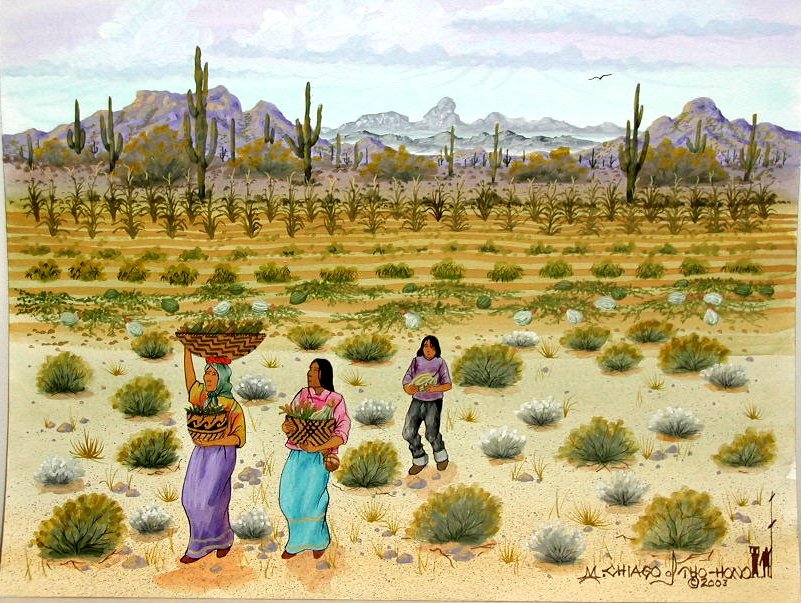

Vegetable Harvest

In this piece,two women and a boy carry beautiful baskets full of corn, squash, melons and devil’s claw, the bounty of cultivated foods that came as a result of summer rains. Summer rain brings the harvest season for the tepary beans, squash and

More

corn. Traditional Tohono O’odham fields were located at the mouths of arroyos where floodwaters deposited fertile silt from the foothills and mountains. Crops were planted in soil made rich by previous seasons of flooding and were irrigated with water from the current season’s rainfall. The Tohono O’odham honored the desert’s rhythms and the desert rewarded their wisdom and hard work with successful harvests. Tohono O’odham farmers grew devil’s claw for making baskets, including those used in the saguaro wine ceremony to summon rain back to the desert year after year.

Michael Chiago was born on the Tohono O’odham reservation west of Tucson. Set against a backdrop of mountains and desert, his artworks depict the traditional gatherings that bring his people together in friendship and prayer. Chiago illustrated the children’s book, Sing Down the Rain, which tells the story of the saguaro wine ceremony. These paintings are part of a series commissioned by Tohono Chul for our Saguaro Discovery Trail that explores the importance of the saguaro for the Tohono O’odham people.

Unknown Navajo Artist

Sandpainting Type Rug with Yeii Figures

Navajo weavings were traditionally made to keep people warm, to protect and cover, and in some cases, to help transport items. They are a very versatile and useful craft and the Navajo have long been masters at creating quality weavings.

More

Early blankets were so densely woven that they were waterproof. This became invaluable to many people in contact with the Navajo, and they could sell their blankets for a small fortune. Before tourists became interested in their use as durable rugs, the patterns were simple and all dyes came from plants and minerals. Since the late 1800’s though, textile weaving has become a highly successful tourist industry. Aniline or commercial dyes were first synthesized in the 1850’s. The natural dyes drawn from plants, animals and minerals produced colors that could be very vivid, and therefore the identification of aniline dyes on a rug is reduced to an educated guess.

The vivid colors of this sandpainting rug suggest the use of aniline dyes. This rug pattern is inspired by the stylized figures of the Yeii. These are the Holy People represented in Navajo sandpaintings. The compositions that medicine men create on the ground with colored sand during curing ceremonies are destroyed the same day. In the beginning, many felt that the representation of these figures in a permanent state was dangerous and even sacrilegious, but a few artists began to weave them in the 1800’s and continues today.

Yeii rugs are very popular due to their symbolic content. There is no religious content to this piece, to maintain Navajo privacy, but they do carry a spiritual theme. Yeii rugs are known to be handspun, synthetically dyed, and usually coarse. The Yeii figures in this rug are long and thin, front facing figures that have healing powers. Male Yeii’s hold a rattle in one hand and crooked lightning in the other, while a female holds a rattle and an evergreen bough. There are two Yeii in the middle of the rug and surrounding them on three sides is the Rainbow Yeii, which is open on the side meant to face east. Between and around the Yeii’s are stalks of sacred plants, corn and tobacco. Because of the corn images, this rug may represent the Blessing the Way, a pattern based on a ceremony for blessing others with a long and good life. The solid border and background are typical of rugs woven in Northern Arizona. Corn was a food staple for daily life. It was an important part of Native American diet. It is known as one of the most versatile foods and can be grown in almost every state in America.

Unknown Hopi Artist

QAA’O Katsina, Corn Katsina

The importance of corn as a life-sustaining staple dates back thousands of years. Anthropologists who have carbon-dated finds at the Tehuacan Valley in Mexico to 5000 B.C., and at Bat

More

Cave in New Mexico to 2000 B.C. have discovered cultivated corn. The great civilizations of the Mayas, Incas and Aztecs had corn deities who they believed bestowed abundant food or withheld a bountiful harvest. According to legend, a Mayan hero named Gucumatz embarked on a journey into unknown and perilous lands to bring an edible plant, corn, to his people. To the Incas, corn was under the patronage of Manco Cápac, god of fertility. The Aztecs associated corn with their god Quetzalcoatl and goddess Zilonen, and they performed elaborate ceremonies and even made human sacrifices to please their corn deities.

In 1492, when Columbus reached the New World, he was introduced to maize, corn. Within a few years, corn had been transported to Europe. The Portuguese later took corn seeds with them when voyaging to Africa, the East Indies, and Asia. By the late 16th century, corn was being cultivated in many areas of the world.

It took centuries for corn to be carried north from Mexico to the American Southwest by migrating Indians. From time immemorial to today, indigenous people have revered corn as a life-sustaining gift. Corn gods, corn maidens, corn mothers, seed-planting ceremonies, harvest rituals, stories, songs and chants are representative of ways for honoring this, the most sacred of plants among Native Americans.

For the Hopi who live on mesas in Northern Arizona, corn is a common theme in katsina songs and is used in many rituals. According to their oral tradition, when the Hopi people emerged from the underworld, they were offered a variety of corn. The Hopi selected a small ear of blue corn, thus determining their destiny. Corn is the traditional measure of Hopi wealth and its ceremonial use is very important. Different colors of corn represent the four cardinal directions.

Unknown Hopi Artist

Rugan Katsina, Rasp Katsina

Markings on each side of this Katsina’s face represent corn, a plant that is very important to the Hopi people. The Rugan Katsina comes in groups, accompanied by corn maidens who play on rasp instruments.

More

The importance of corn as a life-sustaining staple dates back thousands of years. Anthropologists who have carbon-dated finds at the Tehuacan Valley in Mexico to 5000 B.C., and at Bat Cave in New Mexico to 2000 B.C. have discovered cultivated corn. The great civilizations of the Mayas, Incas and Aztecs had corn deities who they believed bestowed abundant food or withheld a bountiful harvest. According to legend, a Mayan hero named Gucumatz embarked on a journey into unknown and perilous lands to bring an edible plant, corn, to his people. To the Incas, corn was under the patronage of Manco Cápac, god of fertility. The Aztecs associated corn with their god Quetzalcoatl and goddess Zilonen, and they performed elaborate ceremonies and even made human sacrifices to please their corn deities.

In 1492, when Columbus reached the New World, he was introduced to maize, corn. Within a few years, corn had been transported to Europe. The Portuguese later took corn seeds with them when voyaging to Africa, the East Indies, and Asia. By the late 16th century, corn was being cultivated in many areas of the world.

It took centuries for corn to be carried north from Mexico to the American Southwest by migrating Indians. From time immemorial to today, indigenous people have revered corn as a life-sustaining gift. Corn gods, corn maidens, corn mothers, seed-planting ceremonies, harvest rituals, stories, songs and chants are representative of ways for honoring this, the most sacred of plants among Native Americans.

For the Hopi who live on mesas in Northern Arizona, corn is a common theme in katsina songs and is used in many rituals. According to their oral tradition, when the Hopi people emerged from the underworld, they were offered a variety of corn. The Hopi selected a small ear of blue corn, thus determining their destiny. Corn is the traditional measure of Hopi wealth and its ceremonial use is very important. Different colors of corn represent the four cardinal directions.

Unknown Tohono O’odham Artist

Man-in-the-Maze Plaque

A flat basket like this one is called a plaque. Since the Tohono O’odham had no use for them, they made them solely for sale. They were made for wall decoration or could be used as a hot plate. The Man-in-the-Maze is a cultural symbol of the Tohono O’odham whose story has many variations. The man at the top of the plaque represents birth and as he goes through the maze, he gets older and his life changes until he reaches the dark center representing death.

More

While many basket makers use commercial dyes to save time, some still use organic and natural materials for the colorful elements of their baskets. Some of the most commonly used plants in the Southwest include:

White – willow, yucca and sumac

Black – devil’s claw

Green and Yellow – yucca

Red – Spanish bayonet root are.

A variety of other plant materials can be utilized to produce dyes includes:

Black – sunflowers seeds and sumac bark

Light rust – lichens and mountain mahogany root bark

Yellow – barberry roots

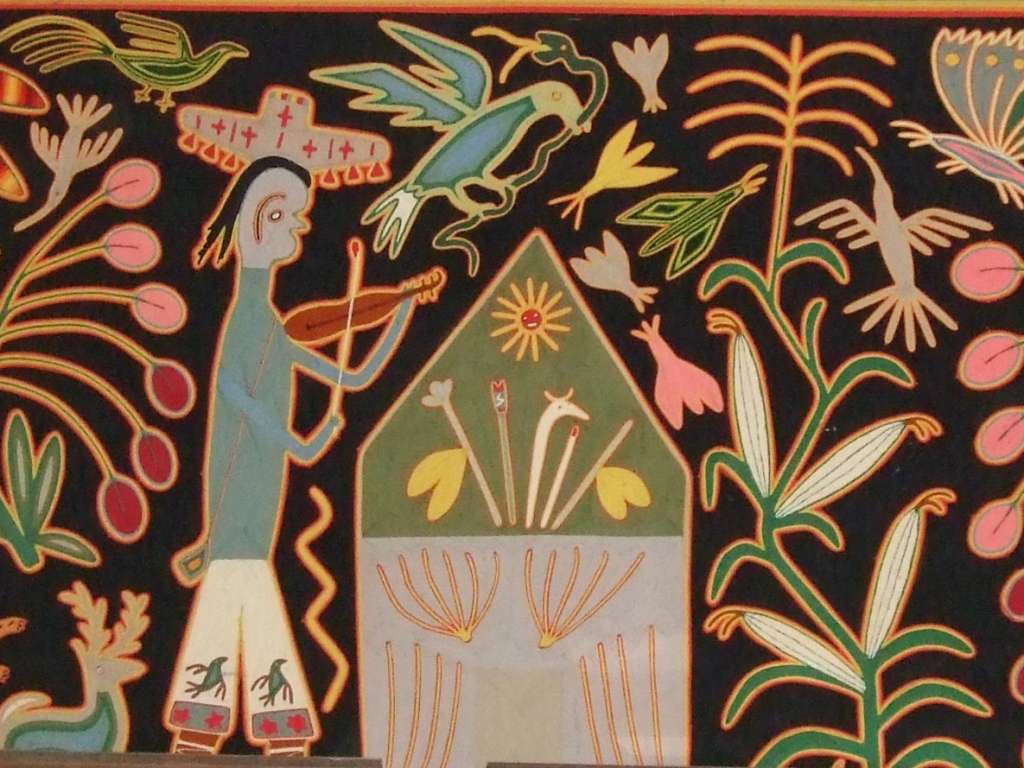

Unknown Huichol Artist

Yarn Painting

Yarn paintings are not sacred but may represent sacred objects, stories or experiences. They are used to teach children about the Huichol culture, as decoration and as an expression of a personal experience. The Huichol are known for their colorful artwork and is said to be where yarn painting originated. The most used symbol is also their most profitable agricultural crop, corn. This Yarn Painting depicts a man with fiddle beside an enclosed space representing the sun with seed sprouting under the earth and shoots springing from the earth. Corn, blooming plants, animals, birds complete the piece representing grown and prosperity.

Day 4 – Artistic Interpretation

Featured Artist – Manual M. Fontes

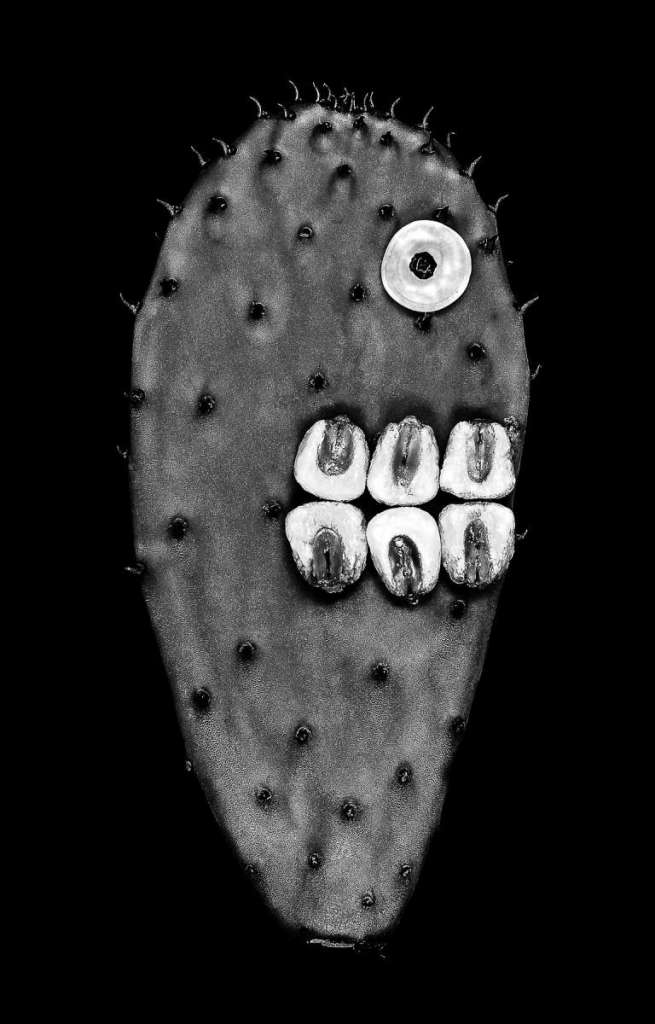

Técpatl

“In this image I depict a freshly harvested Nopal cactus pad as the Aztec Tecpatl. Tecpatl is Nahuatl (the ancient language of the Aztecs) for their broad, lancet ceremonial flint knife. According to Aztec mythology, the Tecpatl was the symbol of sacrifice profoundly associated with the lunar cycle and the harvesting of corn. It was often adorned to look like a human skeleton to represent the connection between life and death, mankind and nature. Without death, there can be no life. This was the belief held sacred by the Aztec. Although the great Aztec civilization has vanished, their mythology lives on in the lives of many Mexican-Americans in the Southwest today. This is especially true with respect to Día de Los Muertos where human skulls adorn festivals, graveyards, and altars dedicated to departed loved ones. Skulls during Día de Los Muertos are not macabre but rather, as the esteemed Mexican poet Jose Guadalupe Posadaonce said, skulls are a reminder that in spite of our mortal pretentions – in death we are all equally dead.”

READ MORE

“My grandmother was born in 1883 in northern Mexico, and was a well-known traditional Mexican-American healer in southern Arizona. Known as a Curandera in Spanish, she healed the sick and afflicted with plants and herbs gathered from the Sonoran Desert. As a boy I spent a great deal of time at her side. Every day she would send me on errands into the desert to gather plants for her medicines. She taught me a great deal about living in harmony with nature. At times I would help my grandmother in her garden. Her garden was a tangled mass of plants, cacti and trees. It was a place where one was welcomed with a fresh coolness and a symphony of herbal aromas. That was the place where she taught me about the Nopal cactus.

My grandmother spoke to her plants and seemed to know each and every one of them intimately as one would know a friend. She told me that the Nopal is a special plant because it sustains life. I never knew what that meant as a boy. All that I knew was that the Nopal was no different than any other vegetable at dinner time; something to avoid. She once said to me, ‘The Nopal gives up part of itself so we can live and by doing so we help it to live.’ A profound statement lost as a child but later found and treasured as an adult. What I now know is that the Nopal has been an integral part of the lives of Mexican-American people in the Southwest for generations. It is part of the legend of the founding of Mexico by the Aztecs, it is depicted on the Mexican flag, has provided sustenance to the poor in lean times and even plays a prominent role in Mexican humor. Today, medical science is starting to discover the value of the Nopal in fighting Type-2 Diabetes.

Corazon (center)

“Pan Dulce (Mexican Sweet Bread) is commonly used to celebrate Día de Los Muertos. On the altars used to commemorate a departed family member one can find in abundance offerings of Pan Dulce. In this image I depict a Pan Dulce as the Sacred Heart. This Christian religious icon symbolizes God’s eternal love. However, love eternal is the central celebratory theme of Día de los Muertos. For many Mexicans, death does not represent the end but the beginning of a different existence. This belief has its roots in the ancient religion of the Aztecs who believed the dead exist on a different plane of reality but are allowed to return to their people once every year. The Pan Dulce in this image is depicted in red. In the ancient Aztec religion, the color red (the color of blood) represents eternal life. During Día de Los Muertos, the color red is found as an adornment throughout the celebration.”

Imagen (left)

“Growing up in Southern Arizona my family celebrated Día de Los Muertos every year as part of a traditional Mexican holiday honoring departed family members. This Mexican holiday has its roots deep in the history of Mexico reaching back to the original peoples of the Americas including the Aztec and Maya. Vital to this celebration is food. Food plays a central role in celebrating Día de Los Muertos because it is believed that on Día de Los Muertos the dead are allowed once again to return to the land of the living to enjoy the foods they once loved during their mortal existence. When my family celebrated Día de Los Muertos, my home was filled with breads, colorful fruits and a variety of vegetables. The air was filled with the savory aroma of traditional Mexican cuisine. It is believed that these aromas have the ability to draw the dead back to their home. My work celebrates Día de Los Muertos by illustrating the complex interplay of Christian iconography and indigenous symbols through the use of traditional foodstuff commonly used to celebrate Día de Los Muertos. This holiday is a complex mixture of Old World Christian tradition fused with the Indigenous Lifeways of Native-Mexicans. My work is illustrative of the fusion of these two worlds.

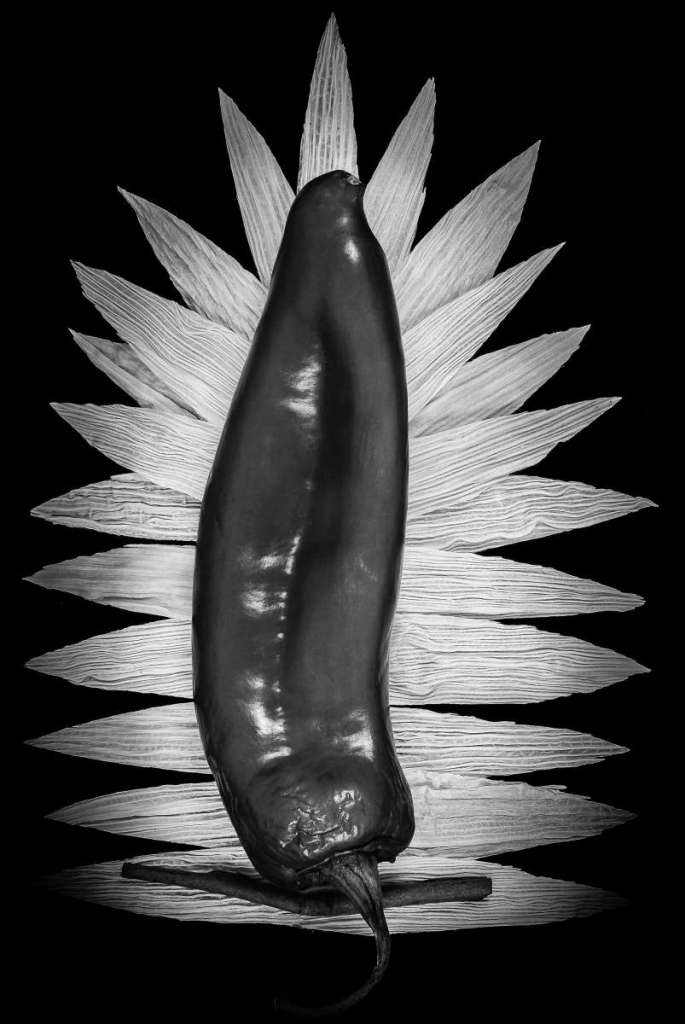

Throughout the Southwest, La Virgen de Guadalupe (The Virgin of Guadalupe) is the most recognizable Mexican religious symbol. Tamales are a favorite food used to celebrate Día de Los Muertos. But two favorites are the green corn and sweet tamales. In this image I take the iconic image of La Virgen de Guadalupe and represent her by using the main ingredients of these two tamales (a green chile and cinnamon stick for sweet tamales) surrounded by the corn husks used to wrap each one. In Mexico, La Virgen de Guadalupe is considered the mother of all Mexicans, so what better symbol to represent the Mexican mothers who always made these tamales for friends and family during Día de Los Muertos.”

Artist Statement

“In the Popol Vuh, the Mayan Creation Myth describes how the Gods created man from yellow and white corn. This connection between food and religion has always intrigued me. As a boy growing up in a Mexican Catholic home I attended Mass regularly with my grandmother. Every Sunday I would sit in the pew with her listening intently to the ancient procession of the Mass but at the same time noticing something quite unique about it. I learned at that time that the Holy Mass was a sacrifice and that we were literally consuming the Body of Christ. A concept I found hard to understand.

Years later, as a young man, I abandoned the teachings of my family and sought other means of spirituality. However, the interwoven nature of Catholicism and Mexican culture are nearly inseparable. By rejecting one, you almost certainly reject the other. I still feel a need to sit and ‘consume’ the culture that feeds my soul.

As an artist my work represents the inter-connection between Catholicism and Indigenous-Mexican iconography and symbolism. I create images using foods I collected from local mercados (markets) and create objects made from these perishable items and photograph them as still life. I love the almost ethereal impermanence of these perishable creations because like my own life, my existence is tenuous and I too shall return to the earth.

I wish to connect the sacred and profane by representing food as sacred object. Why did the Maya choose to represent man as being made of corn? I believe it is because the Maya understood the transcendent importance of corn, the food that represented life to them. They viewed the harvesting of corn as a ‘sacrifice’ and as life itself. My culture, Mexican culture, is life to me. I want to represent the hidden symbols of Mexican culture through the use of food as a representation of its transcendent nature. When I view the food of my culture, I see in it greater spiritual meaning and its symbolic importance in lives of Mexican people.”

Biography

Born and raised in a small mining town in Eastern Arizona, Manuel is a fourth generation Arizonan and Chicano Artist. He studied fine art photography at Phoenix College located in Central Phoenix, AZ and earned his B.A. and M.A. in Cultural Anthropology from Arizona State University. After graduation, Manuel was an Adjunct Professor of Chicano Studies at Mesa Community College for seven years.

Inspired Artists

The Franco Family, from the Tohono Chul Permanent Collection

The Franco Family has a long history of carving dolls from native cacti. The tradition began sometime in the 1940’s with Domingo Franco and his wife, Chepa. Domingo would carve figures from Saguaro Ribs. Chepa would dress them in typical Tohono O’odham fashion, often times they were arranged to reflect the daily routines of the people. Upon Domingo’s death in 1966, Chepa persevered and developed her own distinctive style, working until her death in 1980. Their son, Thomas, and his wife carried on the tradition and developed their own style of carving figures and adding them to unique desert environments made on top of wooden boards covered with sand and various carvings depicting vegetation, structures, and tools.

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Franco

A family of three performs traditional tasks under their ramada. The older woman is shelling mesquite beans to be ground into meal, the younger woman is putting a pot of beans on the fire, and the man is about to have a drink from the dipper near the clay water jar.

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Franco

A couple under a ramada made of saguaro ribs with a cooking stove made from cholla skeleton behind them. There is a mortar on the ground and a jug, possible representing the saguaro harvest.

Domingo and Chepa Franco

A woman is making jam from red-ripened fruit of the saguaro. She has a pot placed over an outdoor campfire to boiling the mixture. The woman has a dipper and wire utensil that she uses to stir or skim the mixture. Two baskets, one on top of another, are at her feet with the top basket being a sieve to filter the pulpy fruit from the liquid that drains into the bottom basket. The Francos cleverly used a natural piece of cholla to represent the sifting basket

[expand title=”MORE FRANCO FAMILY ART” rel=”fiction”]

Domingo and Chepa Franco

A woman grinds dried mesquite beans using a natural stone mortar and a tapered cylindrical pestle. A basket for mesquite flour sits on top of the mortar with another basket storing mesquite beans set at her feet. A woman might spend a whole day gathering and grinding enough mesquite beans to feed one person for five days. Mesquite beans make slightly sweet-tasting flour that is high in calcium, iron and zinc.

Domingo and Chepa Franco

A woman is making bread for a feast, the Wine Ceremony, an anniversary, a wedding, or a wake. The unshaped dough is in a dish to her left with the newly baked bread is raked from the oven and will be placed in the basket to her right.

Chepa Franco

Working together, a couple plows their fields. The woman wears a harness around her waist and pulls the plow while her husband pushes in back, making the furrows to plant their crops.

In the past, the Tohono O’odham farmed their desert lands by using seasonal rainfall and diverting water from rivers and washes. Their traditional crops of tepary beans, squash, corn and melons provided a bountiful harvest coupled with the desert’s wild natural foods including cholla buds, mesquite beans, and prickly pear and saguaro fruit

[/expand]

Michael Chiago

Michael Chiago was born on the Tohono O’odham reservation west of Tucson. Set against a backdrop of mountains and desert, his artworks depict the traditional gatherings that bring his people together in friendship and prayer. Chiago illustrated the children’s book, Sing Down the Rain, which tells the story of the saguaro wine ceremony. These paintings are part of a series commissioned by Tohono Chul Park for our Saguaro Discovery Trail that explores the importance of the saguaro for the Tohono O’odham people.

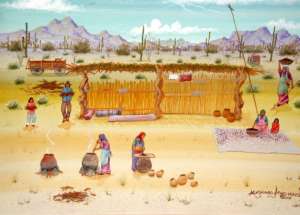

Saguaro Camp

Surrounding a work ramada in the center of the scene, people are busy gathering firewood; cooking, stirring and straining juice; and drying fruit. Traditionally, the Tohono O’odham moved from their winter homes to saguaro camps before continuing

More

on to their summer villages. For weeks they lived among the saguaros harvesting and processing fruit.

Year after year, Tohono O’odham families return to the same sites, where saguaros are plentiful. Some Tohono O’odham families still spend several days or weeks in saguaro camps, while others go on weekends, as their work schedules permit. Just as their ancestors did, they build ramada’s for shade, using mesquite or palo verde for framing and ocotillo, brush, or saguaro ribs for roofing. They may also use modern materials such as lumber and tarpaper. Ramada’s may shelter tables and chairs for socializing because the saguaro camp is a time for visiting with family and friends, as well as a time of hard work

Vegetable Harvest

Two women and a boy carry beautiful baskets full of corn, squash, melons and devil’s claw, the bounty of cultivated foods that came as a result of summer rains. Summer rain brings the harvest season for the tepary beans, squash

More

and corn. Traditional Tohono O’odham fields were located at the mouths of arroyos where floodwaters deposited fertile silt from the foothills and mountains. Crops were planted in soil made rich by previous seasons of flooding and were irrigated with water from the current season’s rainfall. The Tohono O’odham honored the desert’s rhythms and the desert rewarded their wisdom and hard work with successful harvests. Tohono O’odham farmers grew devil’s claw for making baskets, including those used in the saguaro wine ceremony to summon rain back to the desert year after year.

Wine Ceremony

Villagers dance in a circle outside of the Rain House, where the saguaro wine ferments. The medicine man in the center holds up eagle feathers to catch the wind, which will blow in rain clouds. Though few Tohono O’odham practice traditional

More

monsoon farming today, the saguaro wine ceremony remains an important observance—a seasonal cleansing, which restores the people and the land.

Saguaro Harvest

Tohono O’odham men and women gather fruit with saguaro rib harvesting poles called Ku’i’ pads. Women with willow baskets carry and sort the fruit while children gather and sample fruit on the ground.

[expand title=”MORE INSPIRED ARTISTS” rel=”fiction”]

Della Cruz

Saguaro Harvester

This sculpture depicts a person in the act of saguaro harvesting. There is a basket on the base for the fruit, and the figure holds a large stick to pluck the fruit. The first step in preserving the annual harvest is to split open the fruit that is not open already and scoop the pulp and seeds into a bucket while

More

many temptingly sweet and crunchy fruits are eaten on the spot. During the last harvest of the season, the emptied husks are placed on the ground with their red interiors turned toward the sky to hasten the rains.

Della Cruz and her husband Fred Cruz have been partners, creating unique works of art, shared their heritage and provided demonstrations to educate the public regarding all aspects of this Tohono O’odham tradition for over 25 years. Della learned to weave when she was five while growing up in a small rural village near Sells, AZ on the Tohono O’Odham Nation land. Her mother taught her the intricate details of this lengthy process and as Della explored ways of weaving over the years, it became an artistic calling for her. Later, she developed an idea for the three dimensional, figurative basket designs that she and Fred have become known for. Della particularly enjoys creating desert animal figures and likes to incorporate designs reflecting the seasons, such as the Saguaro Fruit Harvest.

Paul Mirocha

Botanical Plat: Saguaro Fruit Study

“I grew up with science because my dad was a professor of plant pathology and I used to visit his lab as far back as I remember. So, it was natural to blend science into my career as an artist and illustrator. I was going to become a scientist myself until I had a brief

More

flash of enlightenment in college while trying to accurately draw a fern leaf. I realized that there are so many things about a subject that one does not truly understand or even notice until you try to draw it.

Part of the joy of illustration is doing the research. Everything involves observation, field exploration, or reading and I consider that as much a part of the work as the pencil or paint. I’ve become an amature botanist, entomologist, and know a lot about weird animals, just from the random subjects I’ve had to illustrate. Because of this, I’ve developed an affection for all these things.

This knowledge of science also deepens my work as a fine artist. In my current role as resident artist on Tumamoc Hill, a research preserve and historical landmark near downtown Tucson, I am reading everything I can about the history of the 1903 Desert Laboratory there, the ecology of the desert landscape, and the archeology of the 2500 years of human prehistory there. It’s all essential to the resulting work.”

To learn more about Mirocha’s site-based artwork, and that of other artists on Tumamoc Hill, go to: www.TumamocSketchbook.com

Sandra Luehrsen

Tree of Life Hot Stuff

Karpos Barbaros

“I came from Chicago to this wild place, Arizona, for a new beginning. I didn’t expect it but the exotic flora fascinated me right from the start. Inspired by the desert, I use earthenware clay, glazes, and fired-in kiln element wire to create my own hybrids. For these works, I incorporated chili peppers into my desert trees of life. Although I prefer salty over hot flavors, chiles gave inspiration for beauty and good humor.”

to learn more about Sandra Luehrsen go to: https://sluehrstudios.com/

Raechel Running

Chile Study No. 1

Chile Fields

“Pick up a chile. Roll it between your fingers, admire it’s color ; fire red and sun baked green; feel its firmness, shape, weight, tender skin; unblemished and perfect. Now close your eyes and imagine how did it get here? Imagine fields of green against the desert horizon. The chile in your hand was tended and picked by other hands; Chile flowers look like workers in the fields. They are small and bright in a sea of green; softer laughter, the crunch of earth, chistes (jokes) and song emanate from the pescadors, the pickers, men and women weave their way up and down the rows. The sun grows strong. It’s particularly humid from

More

the deluge of rain. Once they had to hand drain the field with buckets to save the crop. They are weeding today. In another month they will pick the green, fully matured chiles. In twos month they will pick the red. The chiles will go to a processing plant, be transported across the border and be turned into an organic designer brand salsa served throughout the southwest and major grocery stores.

When I am back in the United States and I miss Mexico, I find myself being drawn to the produce department. I caress the curves of Mexico as I am drawn into the shades of green, red and gold, my hand sensing the ripeness intuitively touching, squeezing the avocados, tomatoes papaya, mangos, the fruits of the Americas bounty in all shapes and sizes. I smell chile and green onions. I close my eyes and inhale deeply. I can still hear Mexican love songs sung in and out over the rows of green in the early morning light. I see the label Hecho En Mexico and remember the fields; the sky; the weather worn faces, their open smiles flash by before me, the memory of brown hands in fertile earth. Strong fingers bend back the veil of leaves revealing the fruit. I think of all the hands whose hard labor make this miracle of life bloom in the desert. I can’t help it when a chile inspired tears fall from my eyes. ”

to learn more about Raechel Running go to: https://www.raechelrunning.com/

Marla Von Ettenberg

Chile Powder

“For this work, I imagined what the intensely flavored powder would look like under a microscope in all its granulated glory, then tried capture it in this sculptural fiber painting.”

Pat Napombejra

Chiltepin

“My painting, Chiltepin, is a surreal depiction of some of the unique features of Tucson and the surrounding area that might not normally be paired together: from the Sonoran desert landscape, to the once deadly

More

intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silo, to the chiltepin plant. The piece speaks to the change in our landscape over time and the resilience of the desert. I chose the chiltepin plant in particular because it grows wild in the Sonoran desert and produces a chili pepper that’s small but packs a lot of flavor and heat, which points to the many ambiguities of this area. Beyond this, I leave it up to the viewer’s imagination.”

to learn more about Pat Napomberja go to: https://www.napombejra.com/

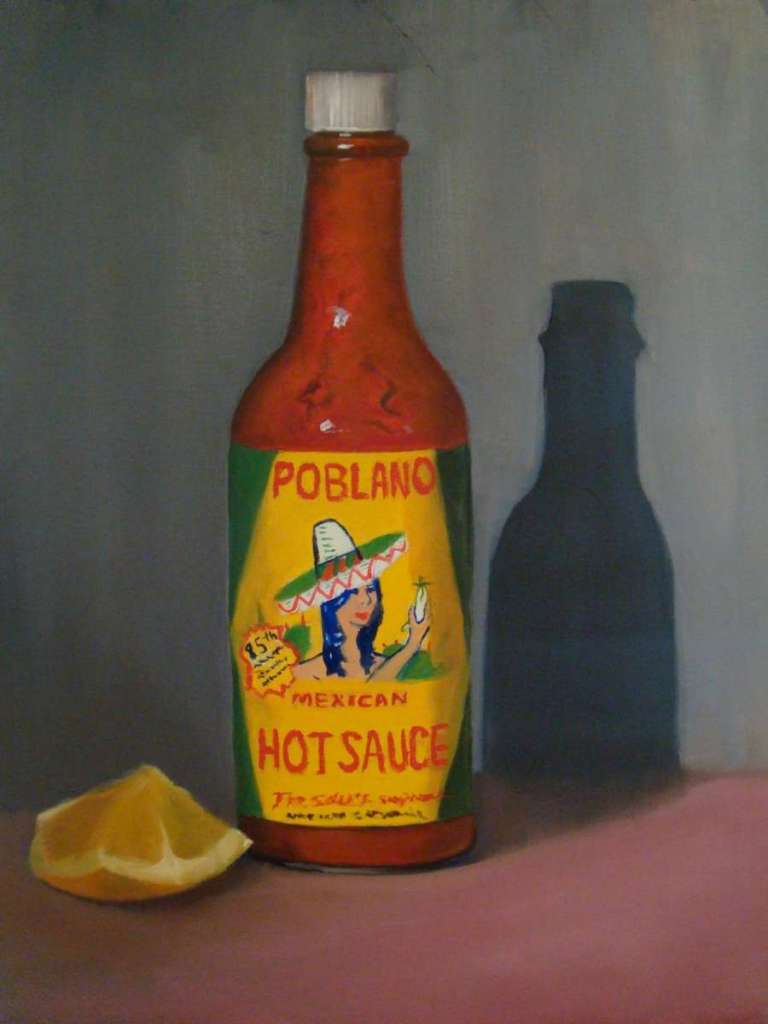

Terri Sullivan

Poblano Hot Sauce

Edible Baja Arizona Article

” As an artist, I find myself inspired by the process of beginning with linen, oils, and brushes and watching as the combination of color, line, and value reveals the hidden beauty of the subject. My goals have been achieved when viewers feel connected to my work and share the enjoyment of being drawn into a painting’s energy and beauty.”

[/expand]

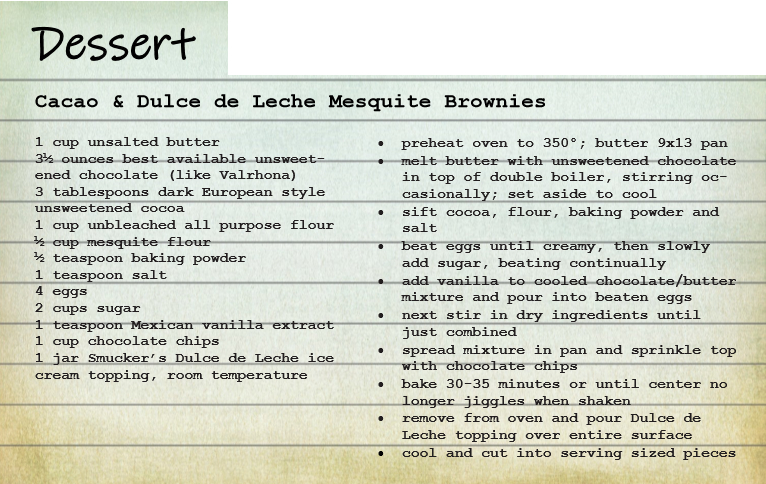

Day 5 – Weekend Inspiration, Getting Cooking

Click on the recipe card below to download the full set of recipes cards featuring native food ingredients!

Next Week’s Theme