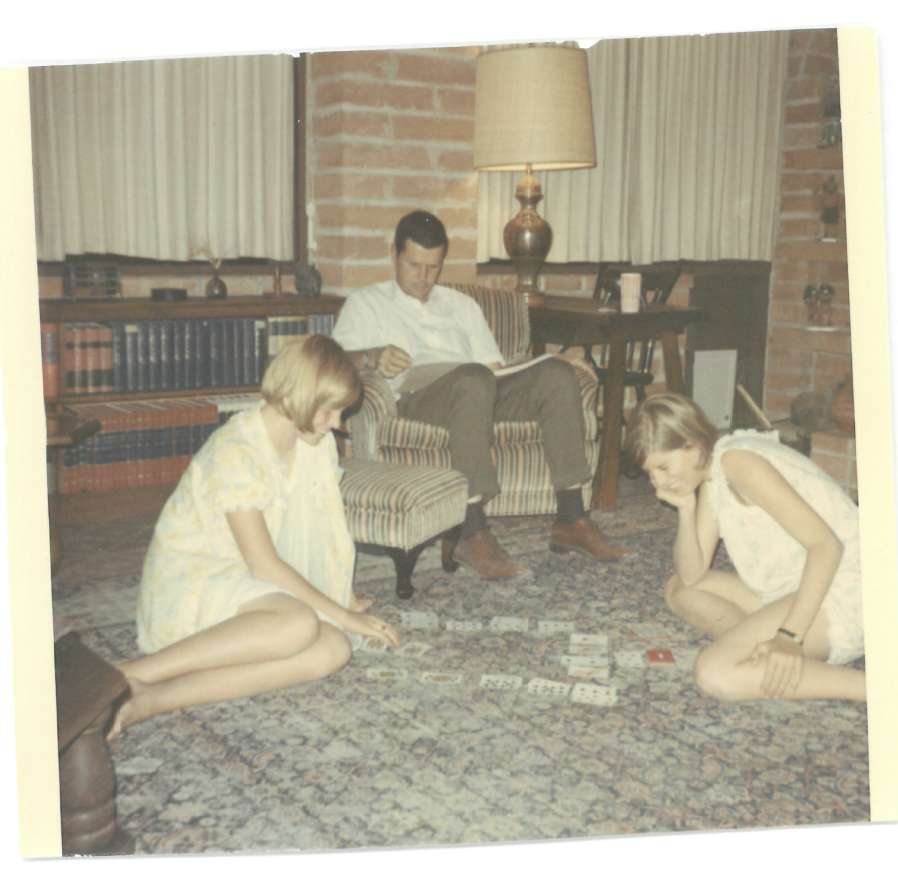

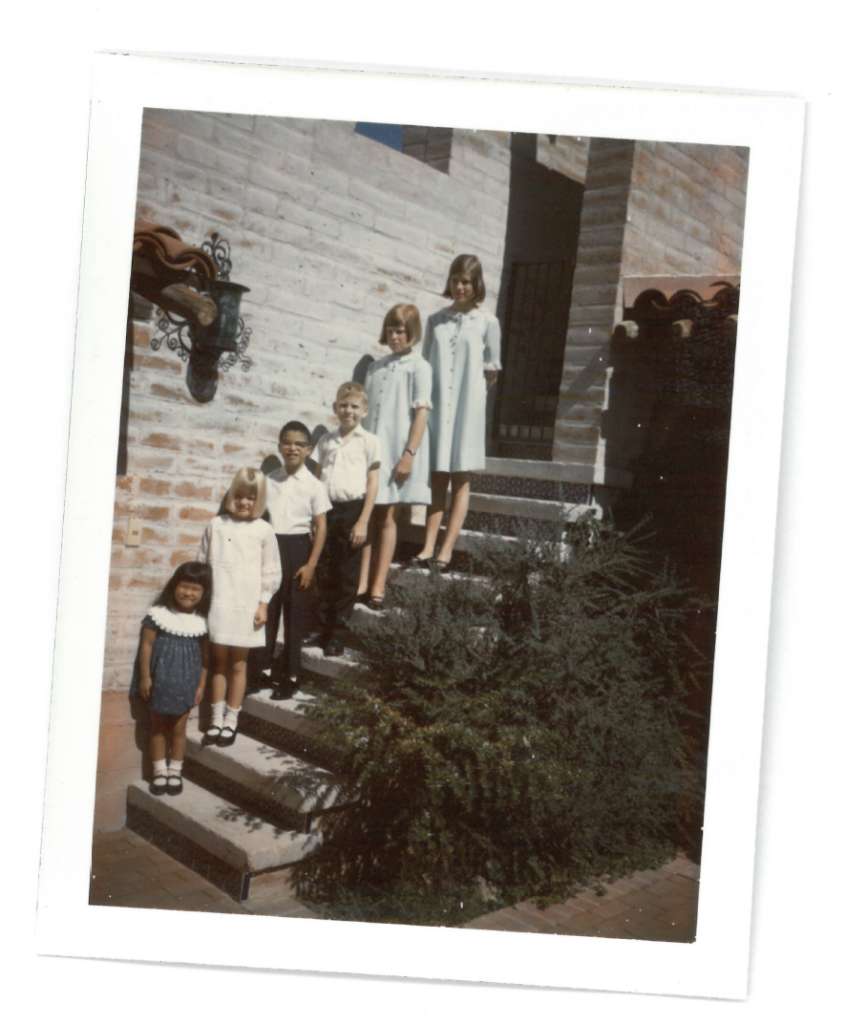

The story of Tohono Chul begins in 1966 when its benefactors, Richard and Jean Wilson, started piecing together patches of the desert that would form its core – ultimately owning 37 acres. In 1968 they purchased the section containing the hacienda-style “West House” known today as the Tohono Chul Garden Bistro (formerly the Tea Room). The Wilsons lived in this house for eight years.

It was during the 1970s that the couple was approached several times by developers seeking to purchase the land for commercial development. They always refused. Jean Wilson told them, “I don’t want to sell the land. I don’t want it cemented over. I want to preserve it.” In fact, when Pima County condemned a strip along the southern boundary of the property in order to widen Ina Road, Dick Wilson demanded that they move every saguaro and replant it on their adjacent property.

After opening the Haunted Bookshop in 1979 on Northern Avenue, the eastern boundary of the site, the Wilsons began planning their next project – a park. “At first, we just went out and put down some lime to make a path and marked the names of some of the plants and bushes, but then it started to snowball.” The path gradually grew into a loop trail meandering a half-mile into the surrounding desert. In 1980, they received a citation from the Tucson Audubon Society for saving the desert green space and opening it to the public.

Tohono Chul Park was formally dedicated on April 19, 1985. “We wanted to keep something natural in the middle of all the (surrounding) development so that people could come easily for a few hours and get out of the traffic and learn something at the same time. It’s probably contrary to what most people would do, but we feel it’s really important for people to have something like this.” An additional 11-acre parcel abutting the property on the north was added in 1995 and the closing of the Haunted Bookshop in 1997 added the final acre, making a total of 49.

At the Park’s dedication ceremony, Richard and Jean Wilson expressed their vision for Tohono Chul:

We dedicate this park to those who come here, who, we hope, will not only admire and find comfort in the natural beauty of the area, but will achieve greater appreciation of the ways of conserving all our precious desert region and obtain a greater understanding of the people native to these areas.

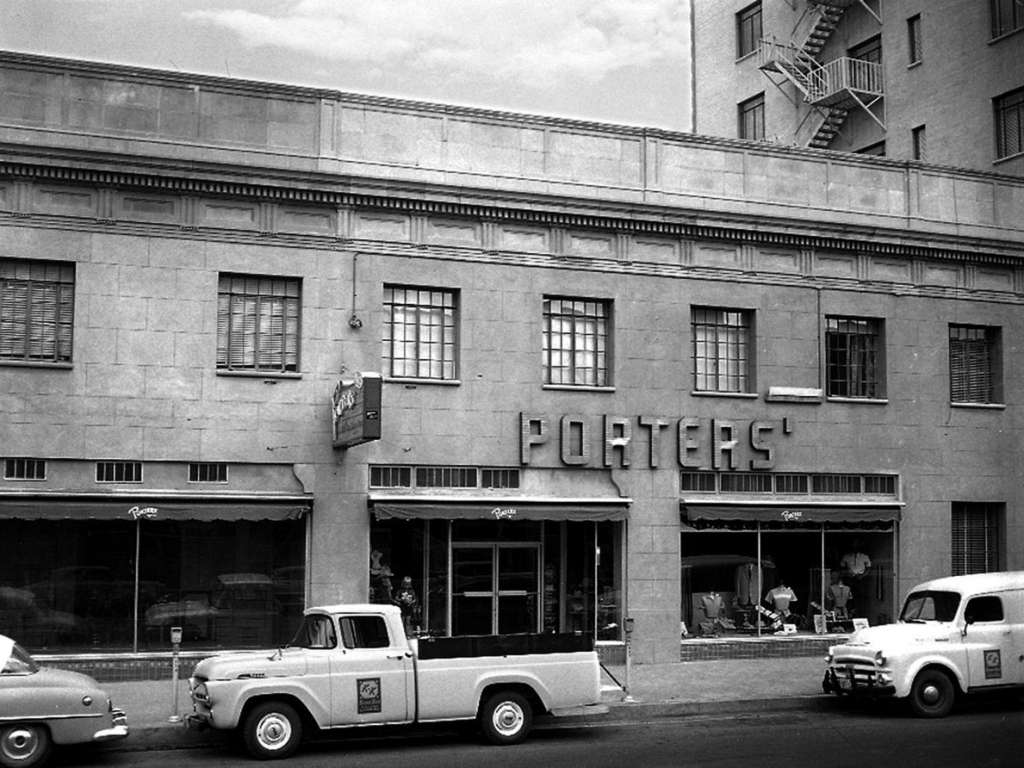

Day 1 – To Know Tohono Chul, You Need To Know Tucson

Click On The Image To Time Warp

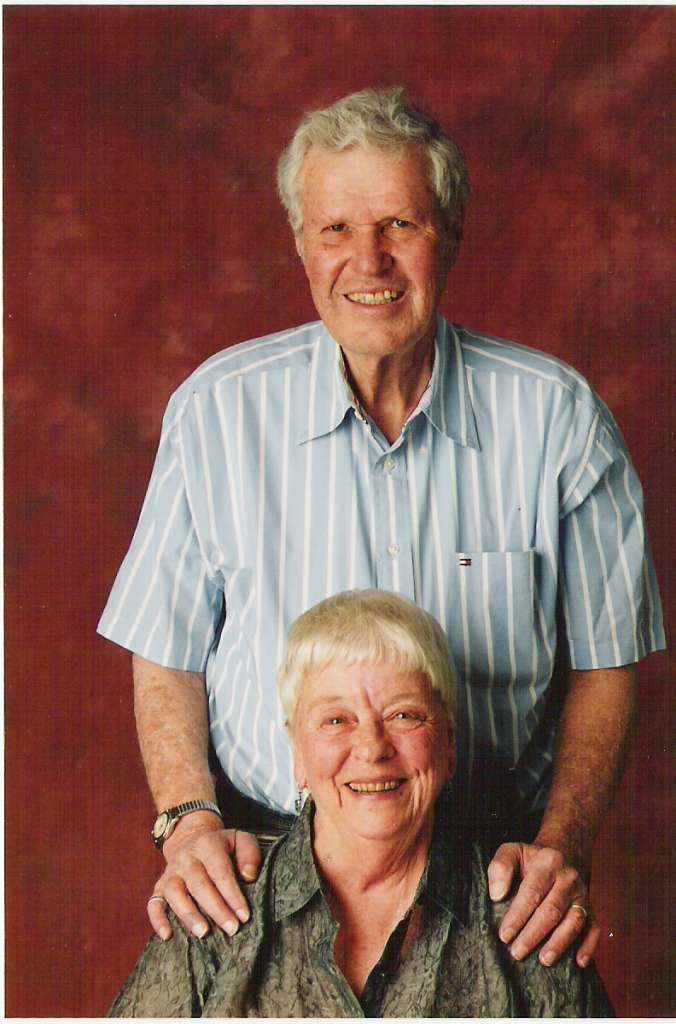

Day 2 – Dick and Jean Wilson

It started with a gift . . .

The son of a Texas oilman, Dr. Richard Wilson trained as a geologist at Yale and Stanford. Working for the U.S. Geological Survey in Colorado, he and his wife Jean made the move to Tucson in 1962 when he took a teaching position at the University of Arizona.

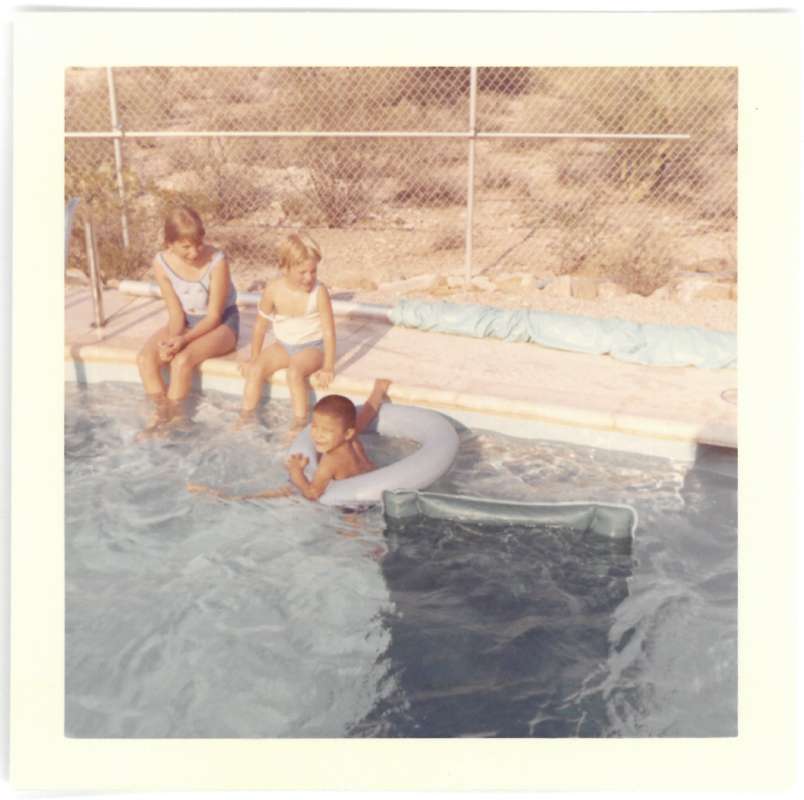

With a growing family, they soon went in search of a bigger house and more room. In 1966 they took a look at “Las Palmas,” an adobe house near Oracle and Ina being sold by John Sullivan, son-in-law of the former owners. Instead, they fell in love with the Sullivan’s own home instead, a Spanish Colonial on Paseo del Norte. In 1968 the Wilsons purchased the original adobe, never actually living in it, offering it instead to a succession of non-profits as a halfway house or youth residence. Over several more years the Wilsons purchased more land from the Sullivan family, by 1977 ultimately owing 37 acres at the corner of Ina and Oracle Roads.

Jean Wilson always wanted to own a bookstore, so an acre at the corner of Ina Road and Northern Avenue was carved out in 1979 for The Haunted Bookshop specializing in books on the Southwest. Daughter Suzie Wilson and husband Todd Horst became the store’s managers.

As an added amenity for customers of The Haunted Bookshop, simple paths were laid out, outlined in lime and spreading into the unimproved desert west of the shop’s parking lot. Concrete picnic tables and benches were added as well.

The Ina Road widening project was underway in 1980 and Pima County set out to condemn a 90’ wide, ¼ mile long strip of property abutting Ina but the Wilsons pushed back. They would agree if every affected saguaro was removed first and replanted on (their) adjacent land. They won. During this time, the Wilsons were also approached multiple times by developers seeking prime northwest real estate for a new shopping center, Tucson and Foothills Malls being under consideration. The answer was “no.” In November, Tucson Audubon recognized the Wilsons for their preservation of desert greenspace.

In 1982, the same year the Muleshoe Ranch goes to the Nature Conservancy, the Wilsons took the next step, creating the non-profit Foundation for the Preservation of Natural Areas whose goals among other things were public education in the history, culture and environment of arid regions in the Southwest, the promotion of water conservation, the establishment of native botanical exhibits and the demonstration of the dynamics between the cultures of this region and their environment.

“We wanted to keep something natural in the middle of all the development so that people could come easily for a few hours and get out of the traffic and learn something at the same time. It’s probably contrary to what most people would do, but we feel it’s real important for people to have something like this instead of just shopping malls.” — Jean Wilson

Tucson builder Ernie Carreon was hired to design and construct the first Demonstration Gardens and horticulturist Matt Johnson was hired to begin installing plantings native to southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico. By 1983 there is a greenhouse, more plant displays and the beginnings of a Geology Wall that will tell the story of the Santa Catalina Mountains.

In 1984 an ethnobotanical garden is added, the original adobe home is repaired and repurposed as the Exhibit House and by the end of the year, the Foundation has a new name — Tohono Chul Park, Inc. The formal dedication is April 19, 1985.

“We dedicate this park to those who come here, who, we hope, will not only admire and find comfort in the natural beauty of the area, but will achieve greater appreciation of the ways of conserving all our precious desert region and obtain a greater understanding of the people native to these areas.” — the Wilsons

Read about the 25th Anniversary of Tohono Chul Park featured by the Arizona Daily Star

Day 3 – Artistic Expression

Enjoy coloring some pieces from our Permanent Collection

Download free coloring pages and art activities highlighting America’s gardens!

See The Originals

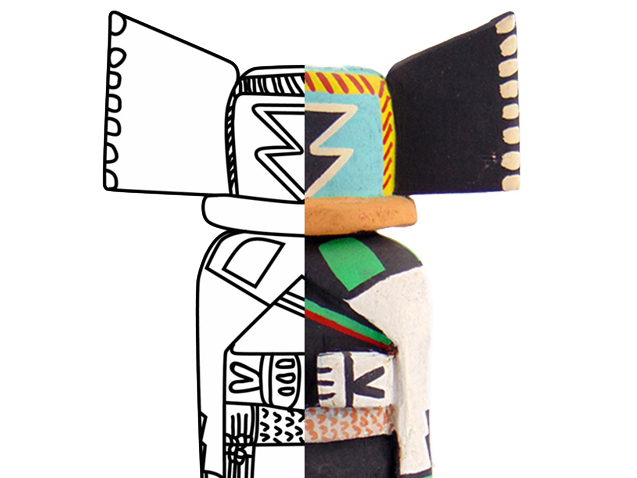

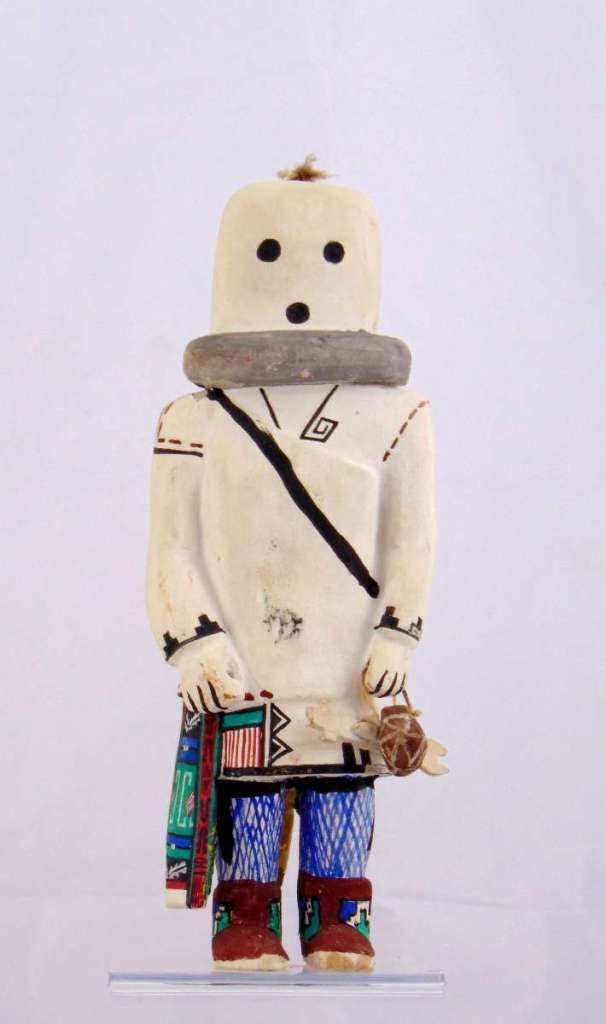

Jimmy Kewanwytewa

Kooyemsi (Mudhead)

Interpretation from Docent Priscilla Herrier from the New Perspectives V exhibition at Tohono Chul, 2019

“The mudhead katsinam were introduced from the Zuni, and sing

Bryan Scott

Tootsa Katsina (Hummingbird)

Tootsa Katsina by Hopi artist, Bryan Scott appears in mixed Katsina dances and is a favorite in the Winter Kiva Dances or Spring Soyohim Dances, especially in a bountiful flower season.

Jimmy Kewanwytewa

Kwaahu Katsina

Interpretation from Docent Midge Berlowe from the New Perspectives V exhibition at Tohono Chul, 2019

“Kwaahu dances with a conscious effort to duplicate the actions and

Henry Shelton

Crow Mother Kachina

Interpretation from Docent Paul Miller from the New Perspectives IV exhibition at Tohono Chul, 2018

“Crow Mother (Angwushahai-i), Crow Bride on Third Mesa, is often

More

on the First Mesa. This is a common katsina with many personalities from leader to clown. At dances, they play games, give gifts to the children, and provide humor for spectators.

This Mudhead has a basket painted on his back and holds a rattle in one hand and a paho, prayer feather, in the other. The katsinam are benevolent spirit beings of the Pueblo tribes of the Southwest. The katsina is not an object of worship, but rather a carving given to educate children in the traditions and beliefs of the Hopi tribe.”

Interpretation from Docent Midge Berlowe from the New Perspectives V exhibition at Tohono Chul, 2019

“Jimmy Kewanwytewa (Jimmy K.) was born in 1889 and was raised on Hopi lands. He began working at the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1931 as a general handyman. Later, he offered carving demonstrations to visitors at the Museum of Northern Arizona and spoke of Hopi beliefs and culture. Jimmy was the first Hopi carver to sign his katsina dolls after encouragement from Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton. At the time, this was very controversial as a katsina doll is a symbol of the Hopi religion. A well-loved employee, he worked at the Museum until his death in 1966.”

To learn more about Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection, go to https://tohonochul.org/galleries/permanent-collection/

More

The Tootsa kachina represents the hummingbird who, according to Hopi legend, intervened on behalf of the Hopi people to convince the gods to bring rain. When dancing, he bobs and calls like a bird while his songs are prayers for moisture to help nourish the crops.

To learn more about Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection, go to https://tohonochul.org/galleries/permanent-collection/

More

movements of the eagle, who, among the Hopi, is treated as an honored guest. Although at one time the Kwaahu dolls were made with real bird wings, regulations to protect these and other birds have forced the artisans to carve wooden feathers.

Jimmy Kewanwytewa (Jimmy K.) was born in 1889 and was raised on Hopi lands. He began working at the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1931 as a general handyman. Later, he offered carving demonstrations to visitors at the Museum of Northern Arizona and spoke of Hopi beliefs and culture. Jimmy was the first Hopi carver to sign his katsina dolls after encouragement from Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton. At the time, this was very controversial as a katsina doll is a symbol of the Hopi religion. A well-loved employee, he worked at the Museum until his death in 1966.”

To learn more about Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection, go to https://tohonochul.org/galleries/permanent-collection/

More

regarded as the mother of all katsinam. Wearing a white bride’s blanket, she leads the initiation of the children during the purification ritual. She emerges from the kiva after Aholi and her Whipper Katsinam are close behind. She carries the yucca whips used by the Whippers on the children entering the katsina cult. Yes, the young are stuck, particularly the ‘bad’ ones. Later in the ceremony, she sings and leads others carrying a basket of corn kernels and bean sprouts hoping to start the new growing season successfully. The Bean Dance ensues in the plaza.”

Henry Shelton is from the village of Oraibi on Third Mesa on the Hopi Reservation. His father was Peter Shelton, Sr. and his brother, Peter Shelton, Jr. were carvers of katsina dolls as well. He devoted much of his life to creating katsina dolls, paintings, and sculptures. He was an employee of the Museum of Northern Arizona and took over for Jimmy Kewanwytewa after he passed away. He is in collections of the Smithsonian, Museum of Northern Arizona, Kansas State Historical Society, Denver Art Museum, Heard Museum and many private collections.

To learn more about Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection, go to https://tohonochul.org/galleries/permanent-collection/

[expand title=”MORE ART” rel=”fiction”]

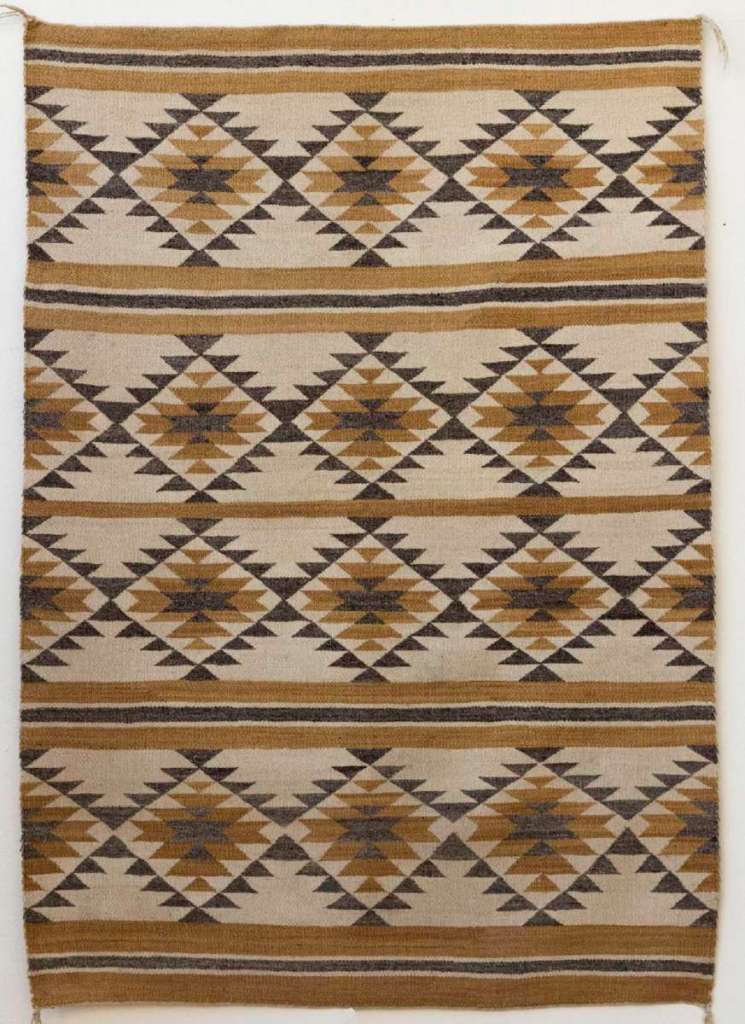

Unknown Navajo Artist

Klagetoh Rug

Klagetoh rugs are similar to Ganado rugs. The difference is in their dominate colors, the Klagatoh rug has a dominantly gray background; depending on the wool it can appear tan or brownish. While Ganado rugs are dominated by the color red.

More

The colors in this rug are black, red, brown and white with an elongated diamond design. The colors are all natural, except for the red and the black may be enhanced by aniline dyes. The name Klagetoh comes from a settlement south of Ganado and it means ‘Hidden Springs.’

To learn more about Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection, go to https://tohonochul.org/galleries/permanent-collection/

Unknown Navajo Artist

Chinle Rug

Chinle Navajo rug with four bands of squash blossom pattern in mustard and gray colors on a natural background and one natural-colored fringe at each corner.

More

A large, exuberantly colored rug was purchased from trader Cozy McSparron of Chinle in 1937. In 1920, the founder of the Wheelwright Museum, Mary Cabot Wheelwright visited McSparron with a proposal that they work together to improve dyes available to Navajo weavers, in an effort to enhance the marketability of their textiles. The Chinle Rug is thought to be a result of their collaboration.

Learn more about the history of Chinle Rugs, visit the Wheelwright Museum website, https://wheelwright.org/exhibitions/tradition-and-tourism-1870-1970/

Unknown Navajo Artist

Sandpainting Rug with Yei Figures

Navajo sandpainting rug with Yei figures and corn design in black, brown, red, green, orange, pink, yellow and gray on natural background. The bright colors suggest aniline dyes.

To learn more about Navajo sandpaintings, go to https://navajopeople.org/navajo-sand-painting.htm

[/expand]

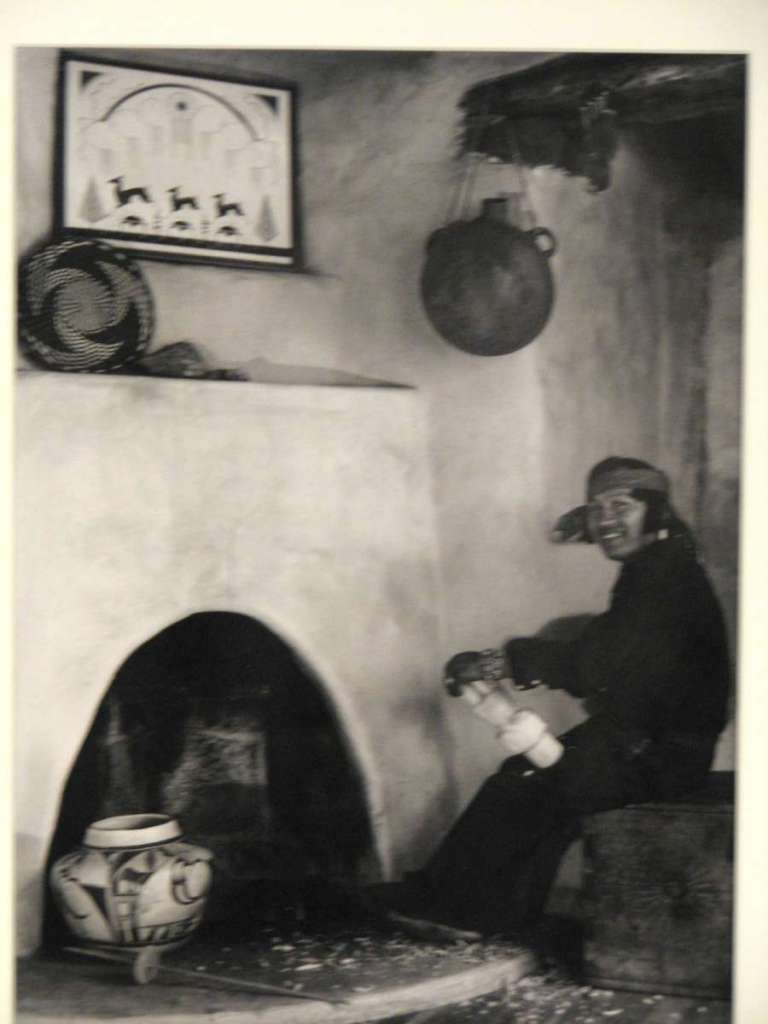

Day 4 – Into the Vault, An Adventure Into Tohono Chul’s Permanent Collection

The Tohono Chul Permanent Collection began in 1986 with a donation of sixty-five objects from the Estate of Mrs. Robert Wilson. Suzanne Colton Wilson was the mother of Tohono Chul founder, Dick Wilson. Suzanne was especially interested in the history, culture, and crafts of the Hopi and Navajo people. She developed a collection of baskets, katsinam, pottery and rugs; many of which were acquired from the exhibitions and markets at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, AZ.

The desire to preserve and exhibit nature, art, and culture is deeply rooted in the Wilson family. Dick’s great, great, great, grandfather was Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), a portraitist of the Federalist Era and founder of the Philadelphia Museum (later the Peale Museum). Opening in 1786 the Museum was one of America’s first major museums. Roughly a century and a half later Harold S. Colton and Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton (Dick’s uncle and aunt) founded Flagstaff’s Museum of Northern Arizona. Today, the Tohono Chul Permanent Collection has grown to include over 350 regional objects ranging from basketry and ceramics to sculptural work and paintings.

[expand title=”READ MORE” rel=”fiction”]

The annual exhibition, Permanent Collection | New Perspectives began in 2015; it features objects from the Tohono Chul Permanent Collection and is curated by volunteers and docents that work closely with the Exhibits Department. Our Guest Curators select objects from the Permanent Collection and contribute statements that share their knowledge and appreciation of the objects they have chosen. Suzanne’s collection is always a significant part of each project. The following objects represent the beauty and breadth of Suzanne Colton Wilson’s original gift – here are some of the favorites that formed the foundation of the Tohono Chul Permanent Collection.

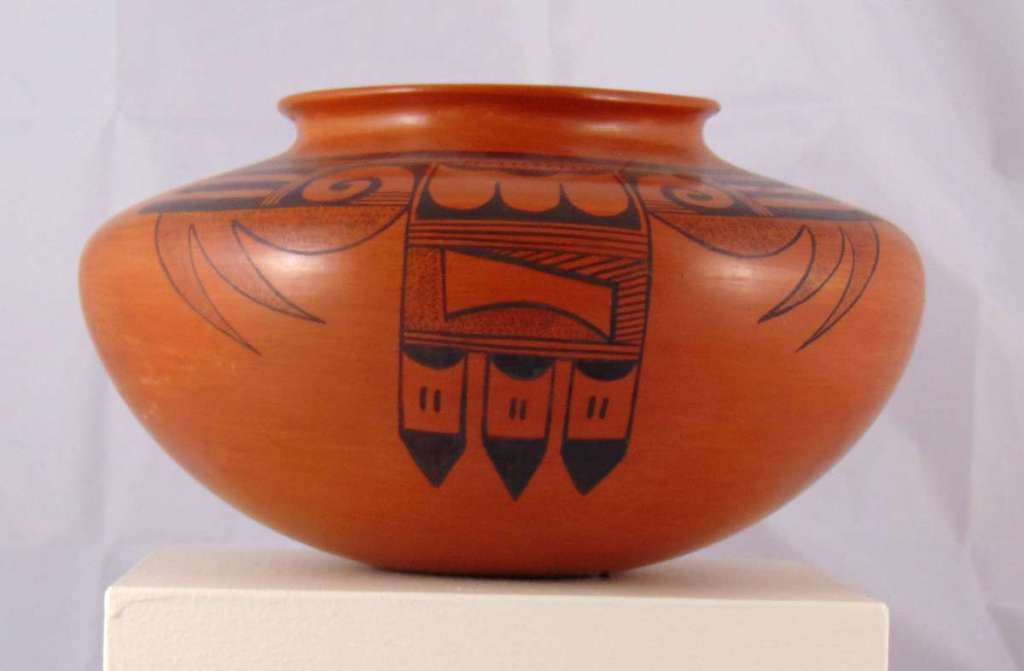

Polychrome Jar

Sadie Adamsredware

jar with black paint

“Sadie Adams (1905-1995) was famous for a variety of pottery shapes and intricately painted designs. She was actively creating pottery jars, bowls, lamps, tiles, cookie jars, plates, cups

More

and saucers between 1930 and 1981. Each piece was coil built, painted with native clay slips and traditionally fired. She lived in the Tewa Village at First Mesa on the Hopi Reservation. Her Tewa name meant ‘Flower Woman’ so each piece was signed with her hallmark of a five-petaled flower. After her husband’s premature death, Sadie supported her young children through the sale of her pottery.

These particular pieces appeal to me because of the elegance of design and the exceptional skill of the artist. The designs and color palette are quintessential Hopi Pottery.”

Suzanne Colton Wilson purchased this jar at the Museum of Northern Arizona. The designs along the shoulder and sides of the jar represent the eagle tail – bird and feather motifs common to traditional Hopi pottery. Paint made from the bee-weed plant was used for the black designs. This wide shoulder pot has the grace and elegance of that period.”

and,

selected by Priscilla Herrier, Docent

from the Tohono Chul exhibition . Permanent Collection | New Perspectives V . 2019

“I am drawn to this piece by the design, which I find clean and simple, much like the designs of Hopi silver jewelry. It reminds me of another pueblo potter, Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo, who created blackware.

Sadie Adams was from the Tewa Village of Hano on the First Mesa, where traditionally pottery is made. She worked at the Hubbell Trading post along with other Hopi-Tewa girls who gained reputations as fine potters. Sadie became a recognized artist, particularly for her decorating abilities reflected in this jar. This jar won First Prize in 1961 at a Hopi Exhibition at the Museum of Northern Arizona.

At the request of Dr. Harold Colton, she made a set of decorative tiles that were set in the walls at the entrance to the Museum of Northern Arizona. Sadie created her pottery in the traditional Hopi way: sanding stones, polishing stones, yucca brushes and her own hands. Her Hopi name means Flower Woman and signed her pieces with a flower on the bottom.”

Jimmy Kewanwytewa

Kwaahu Katsina

painted and carved cottonwood with feathers, straw, beads and yarn

“Kwaahu dances with a conscious effort to duplicate the actions and movements of the eagle, who, among the Hopi, is treated as an honored guest. Although at one time the Kwaahu dolls were made

More

with real bird wings, regulations to protect these and other birds have forced the artisans to carve wooden feathers.”

selected by Midge Berlowe, Docent

from the Tohono Chul exhibition Permanent Collection | New Perspectives V . 2019

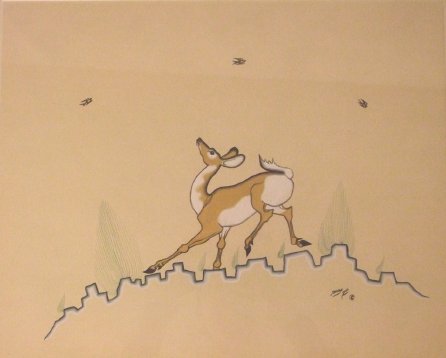

Deer

Jimmy Toddy aka Beatien Yazz

gouache on paper

“Jimmy Toddy was born around 1928 and as a boy, he lived near Wide Ruins Trading Post in Northern Arizona where his father worked as a handy man. Jimmy was a creative child who often

More

drew pictures of desert scenes with crayons on scraps of paper. Impressed with Jimmy’s imaginative drawings, Trading Post owners Sallie and Bill Lippincott encouraged him in his artistic endeavors. The couple even set up a small corner of the trading post for Jimmy to use as a studio, knowing that visitors would enjoy his unique drawing style. By the time he was 12, his drawings were so popular that they were exhibited at the Art Center in La Jolla, California and the Illinois State Museum.

During this period, a friend of the Lippincott’s, Peter Blos, a frequent visitor who often came to Northern Arizona to paint, made a big impression on Jimmy. Blos often worked bare chested, earning him the Navajo nickname “Beatien” (no shirt). Because Blos and Jimmy often spent time together during these trips, Jimmy became known as “Beatien Yazz” (little no shirt).

In the military service during World War II, Yazz joined the Code Talkers, a branch of the marines credited with shortening the war by using the Navajo language to confuse the Japanese.

In the summer of 1947, Yazz attended Mills College to study under the Japanese artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi, which gave him exposure to working with a live model using oil paint.

Following his final return to Wide Ruins, Jimmy has been painting subjects drawn from Navajo daily life for the last 50+ years. Over the course of time he has used watercolor, poster paints, casein and finally acrylic. His treatments have generally been traditional but has shown more modernist works on numerous occasions. His painting are represented in numerous public and private collections and he has won numerous awards throughout his career.”

Eototo Katsina

Jimmy Kewanwytewa

painted and carved cottonwood, feathers

“In 1967, I first encountered the Hopi katsinam at the Heard Museum. Our first purchase among many

More

more was a mudhead (Koyemsi) katsina. In 1970, a Hopi woman I taught at ASU invited my wife and I to the ‘Katsina Night Dances.’ Standing on a roof with our hostess, we watched in awe the procession below.

The Permanent Collection at Tohono Chul is fortunate to have the three principle katsinam that appear at the Powamu Ceremony occurring in February on the Third Mesa of the Hopi Reservation. The Powamu is the third phase of the Hopi Creation – the ‘purification’ ceremony. Rituals include the planting of beans, the initiation of the children, and the bean dance.

Eototo, the Katsina Chief, leads the Powamu from the kiva. He knows all of the ceremonies and the roles of all the participants. He controls the seasons and is highly respected as a spiritual father. He draws cloud symbols with corn flour on the ground. He is always impersonated by a member of the Bear Clan.

Who are the katsinam? The katsinam are not deities. They are the respected spirits of ancestors, plants, animals, and everything else in the Hopi universe. From the winter solstice to the Niman Home Dance in July, they manifest themselves in physical form. The masked men who impersonate them are katsinam as well. They must be above reproach, having only pure thoughts. As the Niman closes, the Katsina Father sends the katsinam home to the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff.”

[/expand]

Featured Artists – Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton & Charles Willson Peale

The Colton Connection

The Wilsons also have strong family ties to the Southwest — its land, its peoples and its cultures.

Dick Wilson’s uncle, Dr. Harold S. Colton, founded the Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff in 1928 as a means of displaying, documenting and preserving the history and cultures of Northern Arizona and the Colorado Plateau. A University of Pennsylvania zoologist, Dr. Colton and his young wife, the painter Mary Russell Ferrell first visited Arizona in 1912 on their honeymoon. This was followed by many summer trips to the state until they moved to Flagstaff in 1926.

Read More

The home of Lowell Observatory and the Arizona State Teachers College (later to be known as Northern Arizona University), Flagstaff was a growing town of young professionals coming west to study the region’s archaeological sites, volcanic fields and tree rings. Artists were drawn by the colorful, wide-open spaces and the endless natural beauty of the Plateau. The Coltons soon became involved in local efforts to create a museum to display the natural and cultural wonders of the region. Dr. Colton was named the first director, a position he held for 30 years, and his wife, the Curator of Art and Ethnology.

Dr. Colton’s wide-ranging interests resulted in scientific studies of Sunset Crater which established its eruption date at 1065 and led to its designation as a National Monument; the application of a Linnean binomial system to the classification of potsherds; a groundbreaking book on field methods in archaeology; and, the use of “taxonomic” methods to classify Hopi katsinam, among many others. His last published study was of the aboriginal Southwestern Indian dog the year of his death in 1970. Noted for its collections and research as well as its exhibits, Dr. Colton encouraged students to visit the museum and intern with staff or pursue independent research.

Co-founder Mary Russell Ferrell Colton, encouraged the Hopi and Navajo tribes in the continuation of their traditional arts, and the development of new styles, with exhibitions and cash prizes. This continues today in the Museum’s summer Heritage Festivals.

Dr. Colton’s sister and Dick Wilson’s mother, Suzanne Colton Wilson, was a collector of contemporary Southwest Native American arts. The donation of 65 pieces from her collection was seed that started Tohono Chul’s own Permanent Collection.

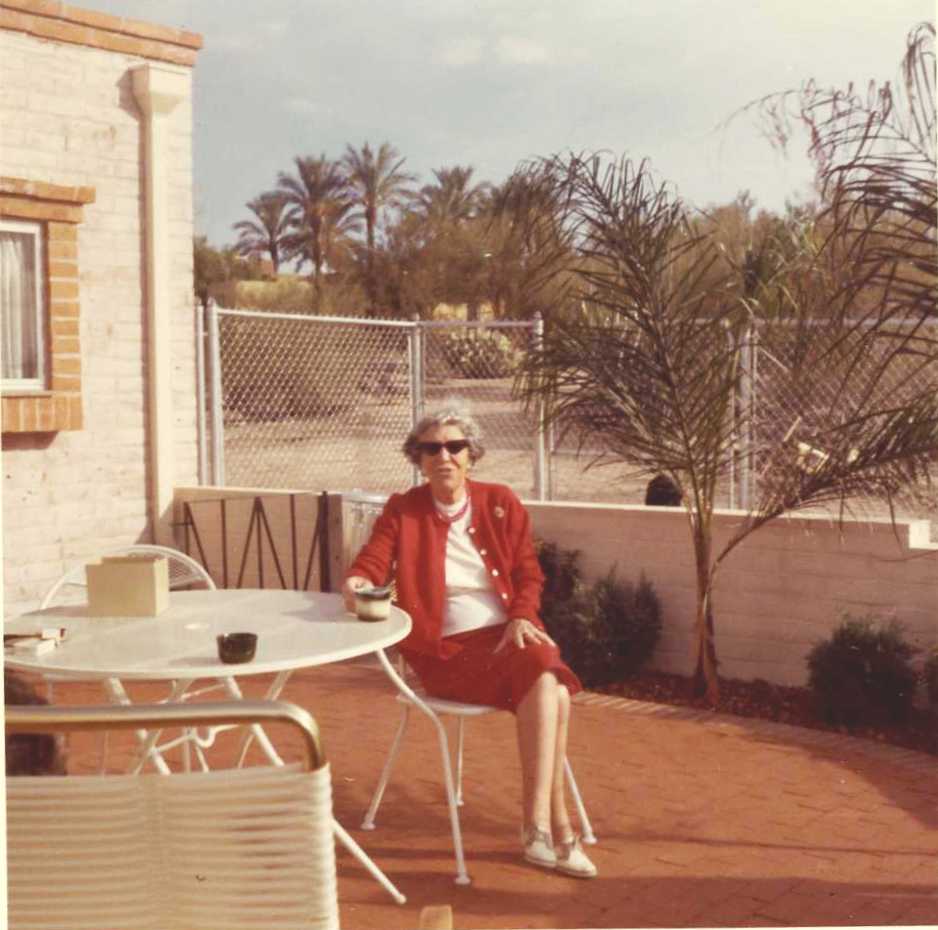

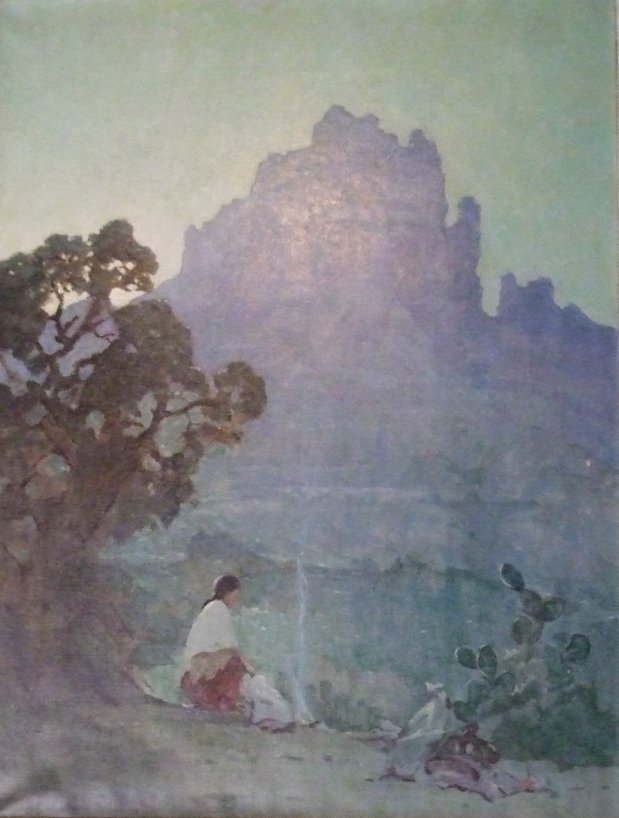

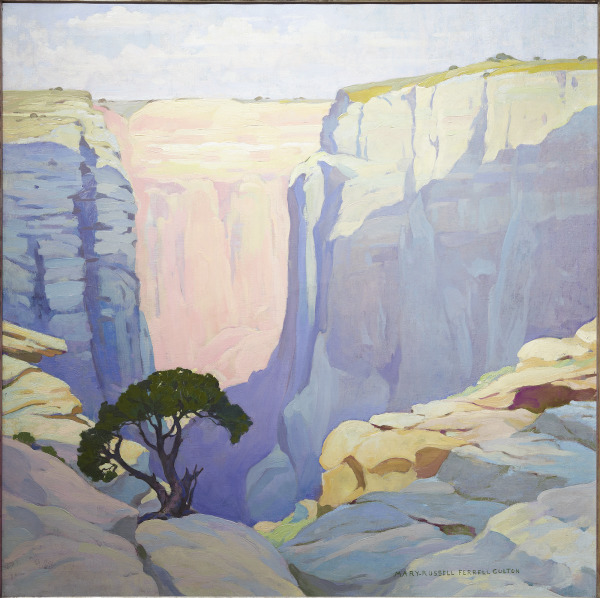

Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton

Courtesy of the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame and the Museum of Northern Arizona

As an Advocate – In 1928 Mary Russell Ferrell Colton and her husband, Harold S. Colton, founded the Museum of Northern Arizona. He became the director; she became the curator of art and ethnology. For more than 20 years the Coltons worked to expand public understanding of the Indian cultures in northern Arizona and of the history of the area. Mrs. Colton, an artist, had a deep appreciation for the arts and crafts of the native people of northern Arizona. She was dismayed, as were many others, to see the traditional skills being lost to the younger generations. Determined to do something about the situation, she collected, cataloged and preserved thousands of Indian artifacts, crafts and works of art. Mrs. Colton researched and wrote papers on the techniques of the Hopi craftsmen, discussing Hopi silversmithing, pottery and weaving.

In 1965 she wrote a book called Hopi Vegetable Dyes. She had spent years discussing techniques with Hopi artists and conducting laboratory experiments to develop effective formulae for the dyes. Her work stimulated a renewed interest in traditional dyes among the Hopi, and the book became an important reference for Hopi artists.

Her interest in art went beyond what she could find nearby. She was undoubtedly one of the first Arizonans to recognize the need for bringing culture to the state. She arranged for special exhibitions of paintings, sculptures and crafts by outstanding artists from throughout the country. And in 1929, she organized the Arizona Artists’ Art and Crafts Show, the first exhibition open to all artists in the state.

[expand title=”READ MORE” rel=”fiction”]

Born on March 25, 1889, in Louisville, Kentucky, Mary-Russell grew up in Germantown, Pennsylvania. When she was 15, she enrolled in the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, the nation’s first art school for women. In 1912 she and her husband came to Arizona on their honeymoon. “We chose northern Arizona because it has so many mountains, and we both like mountain climbing,” she told a reporter. After several summer vacations in the West, they moved to Flagstaff in 1926 and had a Spanish colonial home built north of the city.

Though Dr. Colton had taught zoology at the University of Pennsylvania, after moving to Arizona he chose to specialize in the field of archeology. Mrs. Colton, in addition to serving as curator at the museum, earned a national reputation as an artist. Her interests extended from oil and watercolors to wood carvings and block prints. A story in The Arizona Republic in November 1948 reported she was carving life-size mannequins which would be used to display textiles at the museum. According to the same newspaper story, one of her proudest possessions was an elaborate beam she had carved and painted for use in the Colton home. It was an exact replica of a 1680 Spanish mission beam found in the Hopi village of Oraibi.

Her paintings, including Southwest landscapes and portraits of many of the Indians she met in northern Arizona, were shown to critical acclaim in Philadelphia and New York City. As a graduate of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, she was a member of a group known as “Ten Philadelphia Painters.” Working at the Museum of Northern Arizona, Mrs. Colton initiated a program of artistic events that continues to this day. In 1930 she launched the Hopi Craftsman Show, which had three objectives: to provide a showcase for the best Hopi artists, to stimulate public interest in Indian works, and to provide a financial incentive for the artists to improve their craftsmanship. The show was an unqualified success and has grown in popularity each year.

During the 1930s only a few Hopis were working in silver, and they were producing jewelry similar to that of the Navajo. Mrs. Colton encouraged the Hopis to develop a style which would be uniquely their own. She proposed that their silversmiths use ancient pottery, basket and textile designs to create a distinctively Hopi style of jewelry, a style which became known as Hopi overlay and is extremely popular today. In 1942 the Navajo Craftsman Show began. Like the Hopi show, this event not only benefited the Indian artists but also increased public awareness of their artistic contributions.

As an Artist – Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton was an independent spirit. Her love of art, nature, and Southwestern cultures played a major role in the creation of her artwork and the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, with her husband, Harold Sellers Colton. Deeply committed to her pursuits as artist, educator, ethnographer, curator, and writer, Colton played a vital role in the cultural and intellectual life of northern Arizona. MNA Fine Arts Curator Alan Petersen observed, “Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton’s life and artwork echoed the optimism and modernity of the early twentieth century. Like many other artists and writers during this period, her work reflected the popular romantic perspective of the Southwest. That, and her sense of wonder at the natural world, defined her as an individual and as an artist.”

Throughout her career, Colton painted landscapes, figures, still lifes, and genre scenes. With landscapes outnumbering her other works two to one, they became the basis of her artistic reputation. In her work, the bright palette of impressionists is tempered by the more restrained color and simplified values of Tonalist works.

Tonalism was a popular style in American painting between 1880 and 1920, emerging from the work of a broad range of late-nineteenth century painters. The style emphasized simplified forms; harmonious, muted colors; atmospheric space, and often an element of mystery or melancholy. Colton’s artistic style throughout her creative life ranged from a brighter, more intense palette to a more simplified and muted tonalist one.

Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton enjoyed a long and successful career as a painter, an arts educator, and a curator. Her adventurous spirit and love of nature was reflected in her art and guided her throughout her life. She did much to foster the nascent Arizona arts community and her legacy remains the finest expression of a resourceful individual, who enthusiastically embraced the American West.

Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton died on July 26, 1971, in Phoenix at the age of 82.

[/expand]

Recommended . . .

Listening

The Colton House Sessions, Songs For The Southwest – Produced & Engineered by Todd Phillips

In 2014, Chris Brashear, Todd Phillips, and Peter McLaughlin received a songwriting residency from the Museum of Northern Arizona. Their goal was to create new songs that capture the rich history and incomparable beauty of the Colorado Plateau and the canyon country of the Southwest. Thanks to Flagstaff Friends of Traditional Music and the Museum of Northern Arizona for their commitment to this project and to the arts in northern Arizona.

Reading

Plateau: Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton Artist and Advocate in Early Arizona

“Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton and her husband, Harold Sellers Colton, were the principle founders of the Museum of Northern Arizona. She was an accomplished artist, an educator, a curator, and an advocate. Her vision, her passion for the land and people of northern Arizona, and her bedrock belief that the arts are fundamental to and essential for the education of all people are still core tenets of the museum she helped establish.”

Watching

Mary Russell Ferrell Colton Biography and Paintings with Dr. Mark Sublette

Mary Russell Ferrell Colton was an early artist to Arizona and the Colorado Plateau visiting the state in 1912 and returning each summer until permanently moving to Arizona in 1928. Mary Russell and her husband Harold Colton founded the Museum of Northern Arizona Museum. This video shares a collection of her plein air paintings which are a recent find from the family and now available for sale. These paintings are rare examples of early Arizona artwork done by a classicly trained artist and important historical Arizona figure.

The Peale Perspective – Charles Willson Peale

A love of natural history, the arts and sciences can be traced back to Richard Wilson’s great, great, great-grandfather Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). A true Renaissance man, Peale was initially apprenticed to a saddlemaker as a young man, later taking up watchmaking and silversmithing. But it was as a painter that he found his true calling, first as a student of John Singleton Copley and later, Benjamin West.

Returning to the Colonies from his studies with West in England, Peale developed a reputation as a portraitist, mingling with the notable movers and shakers of the day. An early supporter of independence (once a member of the Sons of Liberty), Peale settled in Philadelphia in 1775 and joined the city militia, serving in the Trenton-Princeton campaign and eventually achieving the rank of Captain. While on duty, he continued to paint, producing miniatures of Continental Army officers, many of which he enlarged into full portraits after the war. Following a term in the Pennsylvania state assembly (1779-1780) Peale finally returned to painting full time. Painting in the Neoclassical style of Jacque-Louis David, he developed a reputation as the most prominent portraitist of the Federalist period.

Completing over a thousand portraits in his lifetime, Peale’s subjects included Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and most famously, George Washington. His 1772 portrait of Washington is considered the earliest of the future President. From this, and six subsequent sittings, Peale painted almost 60 Washington portraits, one from 1779 selling in 2005 for $21 million.

In 1786 he founded the Philadelphia Museum (later the Peale Museum), an institution housed in Independence Hall and intended for the study of natural law and the display of natural history and technological objects. Considered to be the first major museum in the United States, its varied collections included Peale’s paintings, Native American artifacts, and mounted specimens (Peale taught himself taxidermy so as to preserve his bird collection).

[expand title=”READ MORE” rel=”fiction”]

Its most celebrated exhibit was the first complete skeleton of an American mastodon found in New York State in 1801. While the museum eventually closed and its collections scattered, the mastodon remained on display in Germany until the winter of 2019 when it was crated and shipped to the Smithsonian American Art Museum for an exhibition that was slated to open in spring 2020. We all know what happened next.

CHARLES WILLSON PEALE . George Washington . 1779-81 . oil on canvas

collection of THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART . gift of Collis P. Huntington, 1897

On January 18, 1779, the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania passed a resolution commissioning a portrait of George Washington for the Council Chamber and selected Charles Willson Peale as the artist. In preparation, Peale traveled to the Princeton and Trenton battlefields in February of 1779 to make sketches for the background. The original portrait, the full-length version now in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, was a tremendous success and Peale completed numerous copies for royal palaces abroad, each time updating the general’s military dress. This figure of George Washington was probably painted between June and August of 1780. In every other version, Washington is shown after the Battle of Princeton, but here he is depicted after the Battle of Trenton, the turning point of the war. It has been suggested that this portrait was commissioned upon the order of Mrs. Washington, because it is the only portrait in which Washington wears his state sword and because the painting descended in the Washington family.

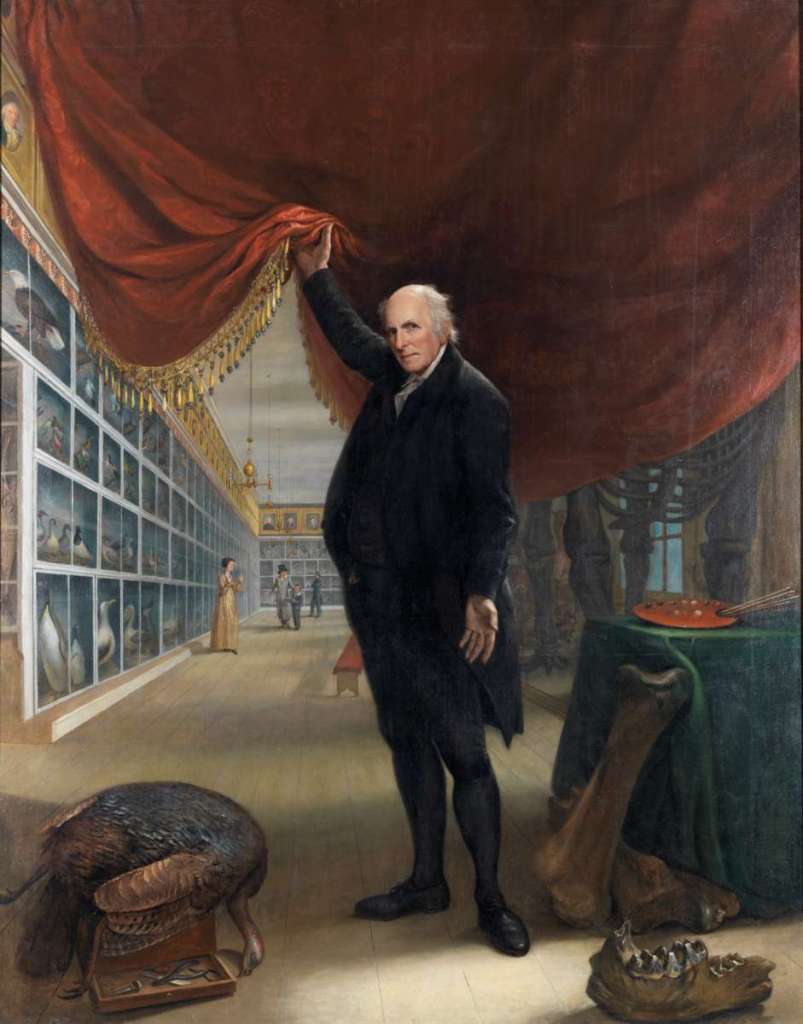

CHARLES WILLSON PEALE . The Artist in his Museum . 1822 . oil on canvas

collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

In his monumental self-portrait, Charles Willson Peale beckons viewers into his museum, which is visible beyond the raised curtain. At the time of the painting, Peale was in his eighties, and at the end of a long career in art and natural sciences. Peale had founded the Philadelphia Museum, the nation’s first museum of art and nature (now permanently closed), in the 1780s. For twenty-five-cents admission, visitors could see more than 10,000 specimens of flora and fauna, as well as portraits of notable Americans.

Peale’s museum reflected early American thought about the established vision of natural order. His displays followed the Linnaean principles of taxonomy, including a portrait of George Washington hanging above an American bald eagle, with songbirds, ducks, and geese—birds perceived as weaker—below the powerful raptor. Further, the inclusion of the dead American turkey awaiting taxidermy in the left foreground of the picture references debates over the national bird.

Opposite the brightly-lit organized exhibition space is a skeleton in the shadows, barely visible behind the curtain on the right side of the painting. Around 1800, most Europeans and Americans doubted that a whole species could go extinct. In a time of nature and nation-building, the discovery of an extinct mammal was unsettling and pointed to an emerging understanding of environmental dynamism and the limitations of the classical hierarchy of nature.

[/expand]

Day 5 – Weekend Inspiration

Delve Deeper Into Tohono Chul’s History – Digital Magazine

[dflip id=”53474″][/dflip]

Delve Deeper Into Tohono Chul’s History – Short Video

Create a Dish Garden

Next Week’s Theme