Birds In Our Backyard

I find the most productive birding areas within Tohono Chul to be the Performance Garden/Sundial Plaza as well as the Riparian Habitat; mostly due to the trees there. The acacias in the Performance Garden in particular and the trees near the Geology Wall. Good migrant visitors in April and again in September/October. – Docent/Birder Ray Deeney

Series One

Click on its name to hear the bird’s song! Click on it again to stop the audio.

Learn More About The Birds

Lucy’s Warbler

Leiothlypis luciae

Chipe de rabadilla rufa

Tiny Lucy’s is the only warbler that migrates to the Desert Southwest each spring to breed and unlike most warblers, these birds are cavity nesters, using abandoned woodpecker holes or openings beneath peeling mesquite bark. To help this declining species, in 2019 Tohono Chul became a test site for Tucson Audubon’s Lucy’s Nestboxes project. Learn more on their website here.

b/w illustration attribution – photo by Budgora

photo attribution – Henry T McLin

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Gila Woodpecker

Melanerpes uropygialis

Carpintero del desierto

In case you’ve wondered who is responsible for those holes in the sides of the saguaro cactus, Gila Woodpecker is the main culprit. Their excavated nests provide protection from predators, as well as blazing summer temperatures, with nest cavities 10 to 15 degrees cooler than outside.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Erin and Lance Willett

sound attribution – Richard C. Hoyer

Yellow-rumped (Audubon’s) Warbler

Setophaga coronate or S. auduboni

Chipe de rabadilla amarilla

Affectionately called “butter butts” by birders for their blazing yellow rump patch, this wood warbler is another winter delight and a VERY well-traveled bird. Ranging from the Caribbean to just south of the Arctic Circle, with errant populations in the UK and the Iberian Peninsula, butter butts are one of the most common warblers in North America.

b/w illustration attribution – JN Stuart

photo attribution – Rubin

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Lesser Goldfinch

Spinus psaltria

Dominico de dorso oscuro

Cheerful little birds, Lesser Goldfinches gather in small flocks other than at nesting time, to feed on a variety of backyard seeds, particularly thistle and from plants in the sunflower family. Their twittery song is common in Tucson backyards, sometimes competing with that of our other resident, the House Finch.

b/w illustration – photo by Carla Kishinami

photo attribution – Erin/Lance Willett

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

Buho cornudo grande

Those are actually stiff feathers, not horns, on the top of this distinguished bird’s head. Great Horned Owls are quite urbanized here in Tucson. At 2’ tall try spotting them on roof tops, telephone or flag poles at dusk when they being hunting for prey which includes rabbits, rodents, snakes, other birds and the occasional small family pet.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Jason Means

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Who cannot be mesmerized by the majesty of this bird? . . . there is something mysterious and wise about it so that no matter how many times I see it, I continue to be awed and delighted when it presents itself, whether I hear its hoot in the night or see it roosting in a tree in the daytime. I had the privilege of having one roost in a tree in my neighbor’s backyard for about two weeks. Every afternoon as the sun got close to setting, it would begin to move. It would stretch one leg, then one wing, then the other leg and other wing – just like it was getting ready for a night of flight and hunting. The stretching and waking up activity would last for about an hour, and sometimes he would move out of the tree to stand on a wall or tall post. But each night just after the sun had set and it was growing dark, it would take off in flight. Even when I saw it for several days in a row, I continued to be fascinated and looked forward to the next afternoon when I could see it again.

– Docent/Birder Carol Massanari

Anna’s Hummingbird

Calypte anna

Colibri de cabeza roja

A common sight in our gardens, Anna’s used to be a migratory visitor to Tucson. The shift from winter visitor to full time resident is likely due to not just the popularity of backyard hummingbird feeders, but, more importantly, the increase in native landscapes that include nectar plants.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Matt Knoth

sound attribution – Richard C. Hoyer

Northern Cardinal

Cardinalis cardinalis

Cardenal norteno

A colorful standout against the colors of desert scrub, year-round resident Northern Cardinal is likely one of our most recognizable birds, particularly the bright red males. Interestingly, juvenile Cardinals do not sport the orange beak of their parents; theirs is actually grayish-black. Entice them to your backyard feeders with sunflower seeds.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Norm Townsend

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

White-crowned Sparrow

Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii

Gorrion de corona blanca

Another “snow bird,” perky White-crowned Sparrow is easily identified by its black-and-white striped crown; juveniles have a brown/gray striped head. Males learn the songs indigenous to the areas where they grow up and song “languages” can form. A male living on the border of two languages may be bilingual, able to sing in both!

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Eric Begin

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Spotted Towhee

Pipilo maculatus

Rascador manchado

Until 1995 known as Rufous-sided Towhee*, this uncommon winter visitor is actually a sparrow! Leaf litter is where you will often find them, scratching up bugs, seeds and fallen fruit using their characteristic, two-footed backward hop. With current warming trends, it is believed we will see fewer Spotted Towhees in the Tucson area. *Eastern and Spotted Towhees were once thought to be the same species.

b/w illustration attribution – Dan Dzurisin

photo attribution – Andrew Reding

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Series Two

Click on its name to hear the bird’s song! Click on it again to stop the audio.

Learn More About The Birds

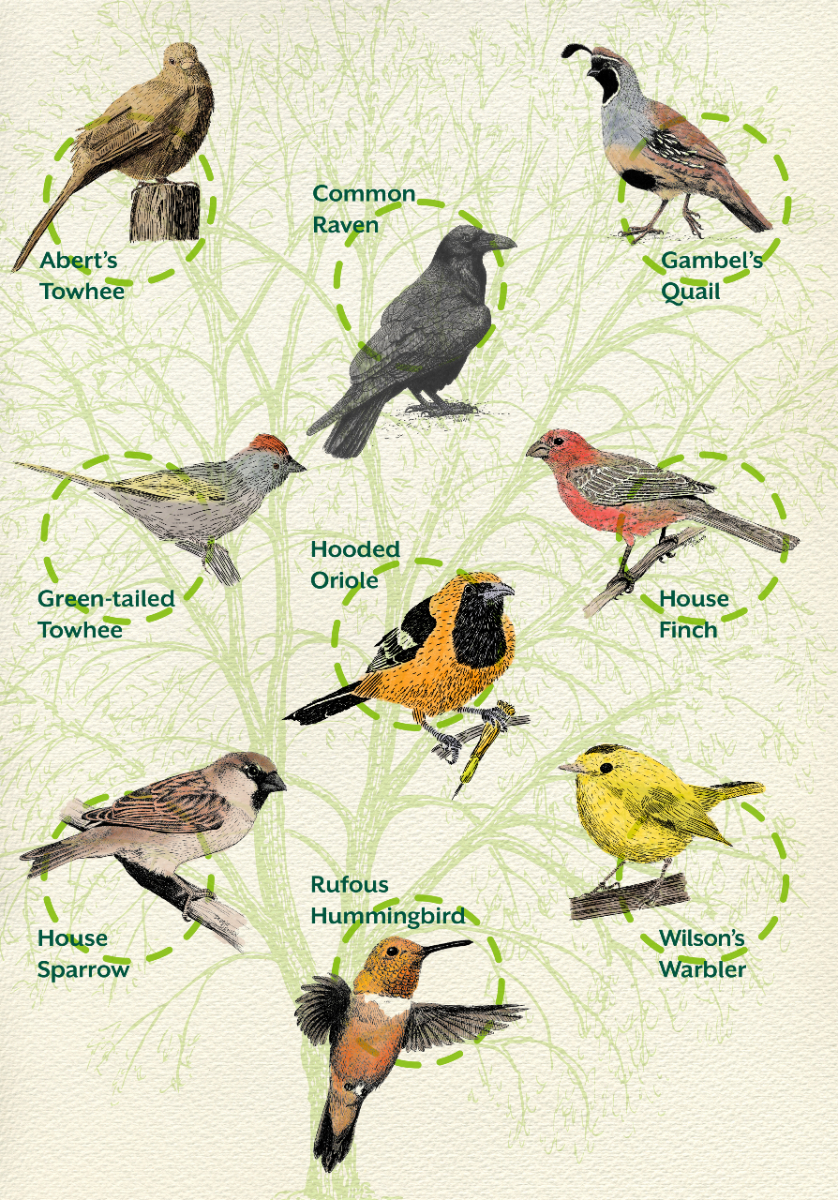

Abert’s Towhee

Melozone aberti

Rascador de Abert

Abert’s Towhee is mostly endemic to Arizona, meaning it isn’t found anywhere else (except along the edges of the state’s borders). Twenty years ago, Abert’s Towhee was rarely seen at Tohono Chul, but we now have at least two resident pairs hanging out in the Desert Living Courtyard and around the Performance Garden. And a group of towhees? They are known as a tangle or a teapot!

b/w illustration attribution – Ben Johnson

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Scott Olsmstead

House Finch

Haemorhous mexicanus

Pinzon mexicano

Native to the Southwest, House Finches, known as Hollywood Finches, were illegally sold in pet shops on the East Coast at the beginning of the last century. In 1940 shop owners released them to avoid prosecution and within 50 years these plucky birds had reunited with their western cousins in the middle of America.

“I always thought of this bird as too “common,” but because it is everywhere, it is easy to hear it cheerfully singing in almost any backyard. It is such a cheerful song that it cannot help but make one smile.” – Carol Massanari

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Jen Goellnitz

sound attribution – Paul Marvin

House Sparrow

Passer domesticus

Gorrion domestic

The other colonization “success” story could be that of the House Sparrow. Originally native to the Middle East, it was introduced to New York in 1852 to combat the linden moth. Hardy, social and adaptable, it is now comfortably ensconced throughout North America and much of the world.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Leon van der Noll

sound attribution – Richard C. Hoyer

Common Raven

Corvus corax

Cuervo comun

If you see a LARGE, black bird croaking its way into your neighborhood, it’s a Raven and not a Crow – Crows aren’t found in Arizona south of the Mogollon Rim. Extremely intelligent and very adaptable, Ravens live just about anywhere and eat just about anything. Graceful in flight, they are noted for their aerial acrobatics.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Rufous Hummingbird

Selasphorus rufus

Zumbador rufo

Belligerent when it comes to defending “his/her” feeder, Rufous hummers are a common sight at backyard feeders during spring and fall migrations. The tiny Rufous, just 3 inches, makes one of the longest migrations, traveling close to 4,000 miles each way between its winter home in Mexico to southern Alaska to breed.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Carla Kishinami

sound attribution – Richard E. Webster

Wilson’s Warbler

Cardellina pusilla

Chipe de corona negra

Another spring/fall migrant, the male Wilson’s Warbler is easily recognized by his little black skull cap – some females may sport a small cap as well. Insect foragers, Wilson’s can be found in the shrubby understory of forests and scrub areas. Always on the move, like flycatchers, they sometimes “sally forth” to catch bugs on the wing.

b/w illustration attribution – Mark L. Watson

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Paul Marvin

Hooded Oriole

Icterus cucullatus

Bolsero enmascarado

You may have spotted this striking, colorful bird stealing sugar water from your hummingbird feeder in early spring. If Orioles are coming to your yard, try putting out halved oranges spiked on a tree branch. Hooded Orioles nest in Tucson, weaving elaborate grass fiber hanging pouches on the back sides of palm fronds.

b/w illustration attribution – Trish Gussler

photo attribution – Jean-Guy Dallaire

sound attribution – Nathan Pieplow

Green-tailed Towhee

Pipilo chlorurus

Rascador de cola verde

A short distance migrant, this Towhee is an uncommon winter visitor to Tohono Chul leaving its higher elevation nesting sites for warmer temperatures in the lower deserts. A two-footed scratcher like Spotted and Abert’s Towhees, you will most likely encounter Green-tailed in the leaf litter searching for insects and seeds.

b/w illustration attribution – Marcel Holyoak (1)

photo attribution – Marcel Holyoak

sound attribution – Garrett MacDonald

Gambel’s Quail

Callipepla gambelii

Codorniz de Gambel

Chi-ca-go-go can be heard every spring as Gambel’s Quail pair up for nesting season. With their distinctive feathered topknots, these quail are ubiquitous in the desert Southwest. Their precocial chicks are cuteness overload. Precocial means that shortly after hatching the young birds are mobile and following their parents.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – CV Vick

sound attribution – Eric DeFonso

Series Three

Click on its name to hear the bird’s song! Click on it again to stop the audio.

Learn More About The Birds

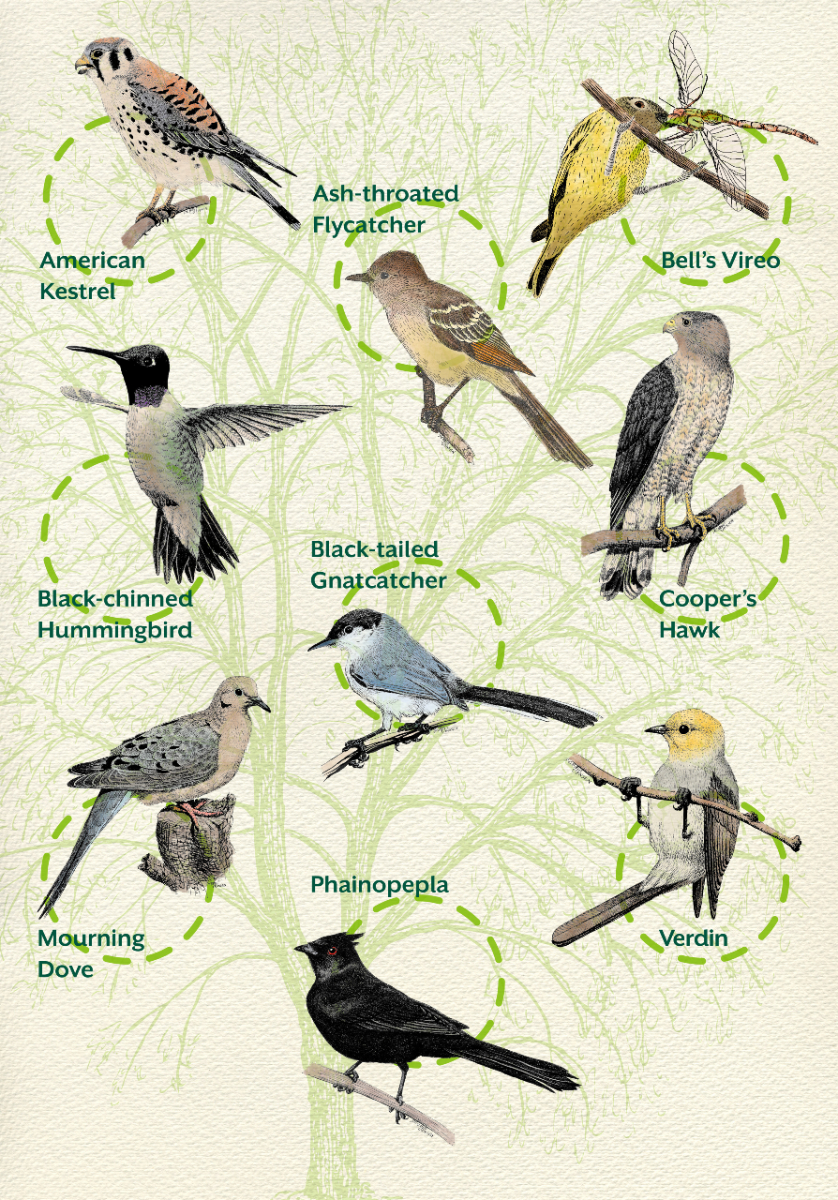

Ash-throated Flycatcher

Myiarchus cinerascens

Copeton Cenizo

Did you know that Ash-throated Flycatcher does not drink water? Very much at home in the desert, it gets all the moisture it needs from the insects it feeds on, catching them “on the fly.” They will also feast on available fruits like saguaro and mistletoe berries. Another cavity-nester, Ash-throated can be attracted to your yard with an appropriate nest box.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Don DeBold

sound attribution – Paul Marvin

Mourning Dove

Zenaida macroura

Paloma Huilota

Their mournful call gives Mourning Dove their name; as recognizable as their call is the whistling sound their wings make on take-off. It’s a wonder that they remain one of the most common birds in North America, given the flimsy nests they build, often just a few twigs and grass stems. When taking a drink, they are able to suck water through their beaks like a straw.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Peter Boesman

Verdin

Auriparus flaviceps

Baloncillo

Tiny Verdin is a bird of the Southwest deserts, endlessly foraging for insects in shrubby trees and bushes. Fairly nondescript in color, their “griege” body is marked by a yellow head and chestnut shoulder patch. Verdin builds spherical nests of twigs and leaf litter, for both breeding and roosting – the male doing the heavy work and the female “decorating” the interior.

b/w illustration attribution – Mark L. Watson

photo attribution – Kenneth Schneider

sound attribution – Peter Boesman

Black-tailed Gnatcatcher

Polioptila melanura

Perlita del Desierto

Common throughout the Sonoran Desert year, Black-tailed Gnatcatcher is an active little bird. Foraging for small insects in shrubs and scrub growth, breeding pairs generally remaining together all year. It is worth noting, these Gnatcatchers usually nest only in native vegetation, avoid areas of introduced plants and are much less common in urban areas than in undeveloped spaces.

“Black-tailed Gnatcatcher – This little bird is often hard to actually see because it flits around so much, but it is easily heard. And it’s distinctive raspy, almost a hiss, sound makes it easy to distinguish from other birds. “- Carol Massanari

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Terry Sohl

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Cooper’s Hawk

Accipiter cooperii

Gavilan de Cooper

A highly skilled flyer, Cooper’s Hawk is at home in wooded areas, maneuvering between branches with ease in pursuit of winged prey. Common urban birds around Tucson, no doubt because of an abundance of pigeons and doves, young hawks are susceptible to a fungal disease carried by doves – word of warning, keep water dishes scrupulously clean and don’t feed large numbers of doves.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Steven Lospalluto

sound attribution – Scott Crabtree

American Kestrel

Falco sparverius

Cernicalo Americano

AKA Sparrow Hawk, American Kestrel is the smallest and most colorful falcon in North American being not much larger than a Mourning Dove. This fierce little raptor can be seen in and around Tucson all year, hunting insects, small rodents and birds. A secondary cavity-nester, it takes advantage of abandoned woodpecker holes.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Dan Dzursin

sound attribution – Richard E. Webster

Bell’s Vireo

Vireo bellii

Vireo de Bell

John James Audubon was the first to describe Bell’s Vireo in 1843, calling it a “greenlet.” The variant species seen in southern Arizona is gray-brown with indistinct wing bars and only a suggestion of yellow along the flank – no green at all. Often heard before it is seen, the Vireo’s song asks and answers – tweedle, deedle, dee? tweedle, deedle, dum.

“Bell’s Vireo – you know summer is close when you hear this bird. I did not know what I was hearing for a long time but when I heard this bird singing, it made me think of the House Wrens I loved hearing all summer when I lived back East. It is a different song, but it sings incessantly and always makes me smile.” – Carol Massanari

b/w illustration attribution – Clark Miller

photo attribution – Erin and Lance Willett

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Phainopepla

Phainopepla nitens

Capulinero Negro

The only representative of the silky-flycatcher family in the U.S., Phainopepla is sometimes mistakenly referred to as the black Cardinal, but they are fruit- and insect-eaters, not seed-eaters. As for the fruit, as many know, they prefer desert mistletoe berries, abundant during the winter months in the Sonoran Desert. They can eat mover 1,000 berries a day!

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Black-chinned Hummingbird

Archilochus alexandri

Colibri Garganta Morada

Warmer weather heralds the return of a Southwest garden regular, Black-chinned Hummingbird. The name comes from the male’s black throat patch, or gorget, which actually flashes iridescent purple in the right light. The color change is caused by light reflecting off microscopic structural features (layered air bubbles) on the feather’s surface.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Carla Kishinami

sound attribution – Richard E. Webster

Series Four

Click on its name to hear the bird’s song! Click on it again to stop the audio.

Learn More About The Birds

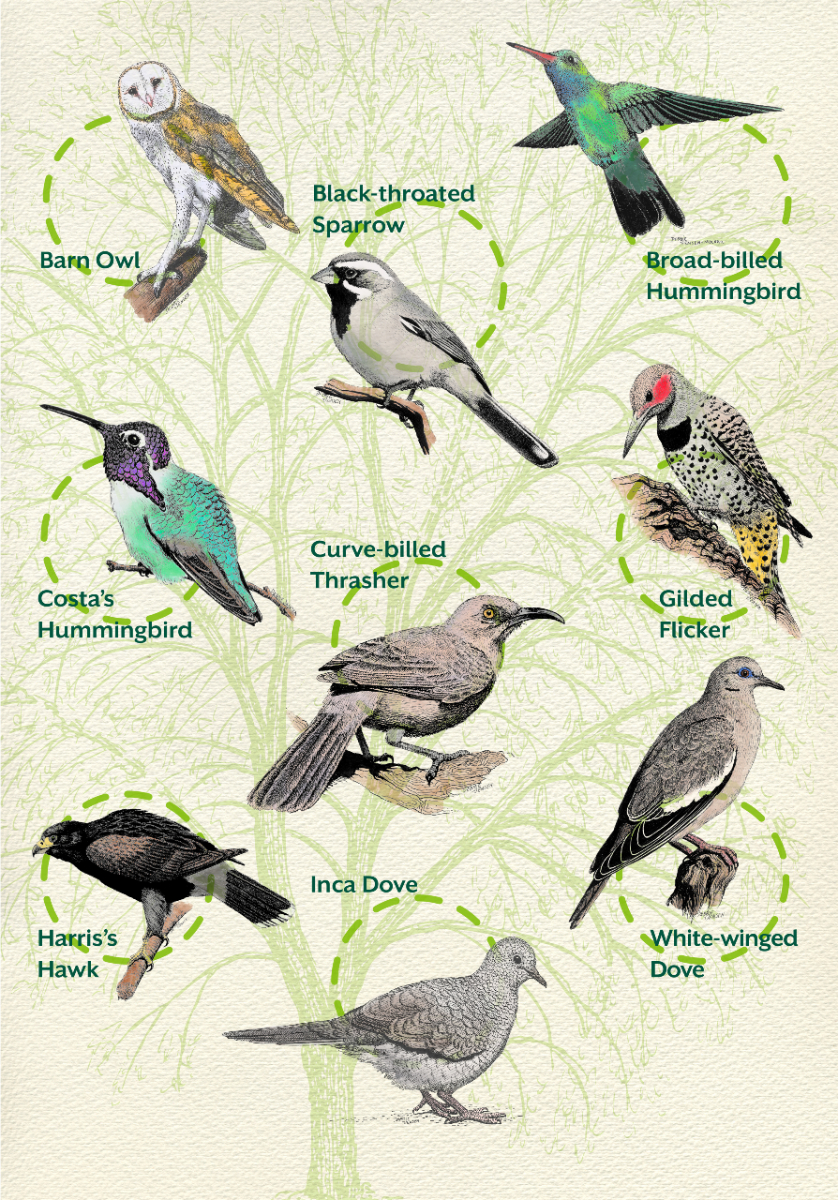

Costa’s Hummingbird

Calypte costae

Colibri de Cabeza Violeta

Another springtime visitor is Costa’s Hummingbird, the flashy male modelling a sweeping, bright purple mustache, the Yosemite Sam of the hummingbird set. As is the case with other hummingbird species, once a male’s aerial displays have attracted a female, she is left to build the nest and raise the young on her own.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Inca Dove

Columbina inca

Tortola de Cola Larga

Found only in the desert Southwest, petite Inca Dove prefers urban areas and is not shy around people. Its “scaled” feathers distinguish it from the two other dove species found around Tucson; when in flight, its underwings are cinnamon. Not particularly tolerant of cold temperatures, global warming seems to be allowing it to expand its range northward.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Gilded Flicker

Colaptes chrysoides

Carpintero de Pechera de Arizona

Those nest holes higher up in a saguaro are likely the work of Gilded Flicker. It is thought that because Flickers need larger nest cavities, and their beaks are not as suitable for heavy excavation, they choose the upper reaches of the cactus where ribs are thinner and they break through them on their way to the center of the plant.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Pete Morris

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Barn Owl

Tyto alba

Lechuza de Campanario

Ghostly pale Barn Owls are found pretty much worldwide, subspecies varying in size, coloration and markings; our North American subspecies is the largest. Increased loss of habitat has resulted in declining numbers of these owls in many parts of the country. Drawn to live in barns and abandoned buildings, the installation of nest boxes has helped in some places.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Katie Moore

sound attribution – Dan Lane

Broad-billed Hummingbird

Cynanthus latirostris

Colibri de Pico Ancho

Board-billed Hummingbird ventures north in to mid-level elevations in southern Arizona to breed each spring, heading south again when the weather cools. Males are an iridescent blue-green with bright orange-red beaks tipped in black; females are a pale gray in contrast. Their diet includes not only nectar from native flowers and the sugar water from feeders, but insects and spiders.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Paul Marvin

Curve-billed Thrasher

Toxostoma curvirostre

Cuitlacoche de Pico Curvo

A year-round resident of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, Curve-billed Thrasher is a medium-sized bird with a watchful orange eye and strongly curved beak used to toss aside leaf litter in the quest for insect prey. Thrasher parents build often build their nests in clumps of cholla for the added protection of the cactus spines. More than one twiggy construction may be built before one is selected for the nursery.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – CV Vick

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Black-throated Sparrow

Amphispiza bilineata

Gorrion de Garganta Negra

Birders often refer to sparrows as LBJs, “little brown jobs,” but not this one. Black-throated Sparrow’s striking white facial stripes and black throat patch are unmistakable. A resident of scrubby desert, it forages for seeds and insects on the ground, or at a backyard feeder well away from the suburbs.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Julio Mulero

sound attribution – Scott Crabtree

Harris’s Hawk

Parabuteo unicinctus

Aguililla de Harris

You will never forget the sight – a single Harris’s Hawk is perched on a saguaro or telephone pole and one or more additional birds will fly in and stand on its back. It’s called “stacking” and it may be a way to get a better look around. Or, they just want its perch! These very social raptors hunt cooperatively as well, several waiting on the backside of a bush as another flushes their prey.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Guy Dallaire

sound attribution – Robin Carter

White-winged Dove

Zenaida asiatica

Paloma de Ala Blanca

The largest of our common doves, White-winged Dove only visits during the summer months – its repetitive “who cooks for you?” is a sure harbinger of warmer temperatures. Fond of saguaro flower nectar and the resulting fruit, it has been established that in addition to nocturnal nectar-feeding bats, White-wings play a major role in saguaro pollination.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Diana Robinson

sound attribution – Frank Lambert

Series Five

Click on its name to hear the bird’s song! Click on it again to stop the audio.

Learn More About The Birds

Ladder-backed Woodpecker

Dryobates scalaris

Carpintero Mexicano

Not quite as common as Gila, Ladder-backed Woodpecker is perfectly at home in the deserts of southern Arizona and its smaller size means it’s comfortable nesting in mesquite or hackberry. Ladder-backed forages for insect larvae by tapping and probing cracks in bark, right-side-up or even hanging upside down. Both adults are basically striped and spotted black-and-white, with the male sporting a red crown.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – JN Stuart

sound attribution – Paul Marvin

Greater Roadrunner

Geococcyx californianus

Correcaminos Norteno

Beep-beep – not. But, Greater Roadrunner (yes, there is a Lesser that lives in Mexico and Central America) can still outrun you and kill a rattlesnake and eat it for dinner. Not as common in more urban areas, foothills residents may be treated to occasional sightings. Roadrunner’s speed is helped by its zygodactyl feet – two toes facing front and two back allowing for better gripping – a trait it shares with woodpeckers.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Brit

sound attribution – Eric DeFonso

Turkey Vulture

Cathartes aura

Zopilote Aura

One of the few birds with a sense of smell, Turkey Vultures are summer visitors to our area. As the surrounding air warms each morning, you may spot a “kettle” of Vultures taking advantage of rising air currents to ride the thermals high into the sky, soaring with wings held in a “V” shape. As for the reddish, bald head, an absence of feathers means a head that is easier to keep clean after dining on carrion.

“Turkey Vulture – the beauty of this bird is in its soaring. It is easily identified by the way it catches the air waves and soars for long periods of time without a flap of the wing. It is easily distinguished from the ground by the two tones of its underwing – the upper part of the wing being dark (black) and the lower part of the wing appearing more silver or grey in color.” – Carol Massanari

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – unknown

sound attribution – Andrew Spenser

Brown-crested Flycatcher

Myiarchus tyrannulus

Copeton Tirano

A little larger than Ash-throated, Brown-crested Flycatcher makes its way to southern Arizona late in the breeding season and has to aggressively compete for much-coveted nesting holes. The upside of showing up then is the abundance of newly emerged cicadas and grasshoppers. Oh, and a group of flycatchers is a “zipper!”

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Henry T McLin

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Northern Mockingbird

Mimus polyglottos

Cenzontle Norteno

The great mimic, a male Northern Mockingbird can have a repertoire of hundreds of songs – original compositions and riffs of those of other birds. These birds are very territorial and the singing competition can go on all day and even into the night during nesting season. Watch for two, flashy white wingbars when the wings are jerkily fanned open while perched.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Henry T McLin

sound attribution – Pat Goltz

Western Screech-Owl

Megascops kennicottii

Tecolote Occidental

Following the bouncing call! The cascading hoots of a Western Screech-Owl sounds like a bouncing ball. Small owls (less than 10” tall), Screech-Owls are opportunistic carnivores eating a variety of desert creatures from invertebrates to birds to mice and even bats, which they will catch on the wing. Cavity nesters, they will occupy abandoned saguaro holes or an appropriate nest box in your backyard.

“I remember Tucson Audubon installing a nest box with the hope of attracting a Kestrel. Part of why that location was chosen was the excellent shade provided by the mesquite protecting it from harsh eastern sun exposure. Well, as they say, the best laid plans . . . The mesquite collapsed shortly after we put up the box removing all shade protection for any potential bird to be attracted to. I figured, well those are the breaks and we can forget about any bird finding that box appealing. But lo and behold a Western Screech-Owl starting roosting in the box. Unexpected and not our original target bird, but that just reinforced the beauty of the unexpected and unpredictable aspect of nature. If you think you can predict outcomes, you’ll be humbled by what nature has in store. It doesn’t care about your expectations. And that’s wonderful and something that keeps us coming back for more.” – Ray Deeney

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Bryant Olsen

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Cactus Wren

Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus

Matraca del Desierto

The state bird of Arizona is the fearless Cactus Wren, the largest wren in the U.S. Streaky and spotted, adults have a deep red eye beneath a very conspicuous white brow line, while juveniles’ eyes are brown. Their football sized nests are built in prickly pear and cholla as well as thorny shrubs. Not just for raising young, adults will also construct just for sleeping.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Jo Falls

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Pyrrhuloxia

Cardinalis sinuatus

Cardenal Desertico

Not to be mistaken for a female Cardinal, Pyrrhuloxia is more adapted to life in the dry scrublands of the Sonoran Desert. Note the longer, wispy crown, red mask (as opposed to black) and the yellowish, parrot-like beak. Pyrrhuloxia is also a seed aficionado and will happily visit backyard sunflower feeders next to their Cardinal cousins.

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – Clark Miller

sound attribution – Scott Olmstead

Red-tailed Hawk

Buteo jamaicensis

Aguililla Cola Roja

That recognizable primal raptor “scream” that echoes across every desolate scene in a Hollywood western is Red-tailed Hawk. The most common hawk in North America, Red-tails are most likely to be seen on the outskirts of urban area perched atop telephone poles on the lookout for rabbits and other small mammals. Oh, and not all Red-tails have red tails . . .

b/w illustration attribution – Debbie Jensen

photo attribution – TC Davis

sound attribution – Eric DeFonso